Corresponding Author: Mark J. Turner

Department of Physiology, McIntyre Medical Sciences Building, McGill University, 3655 Promenade Sir William Osler, Montréal, QC, H3G 1Y6 (Canada)

Tel. +1 514 398 4323, E-Mail mark.turner2@mcgill.ca

Phosphodiesterase 8A Regulates CFTR Activity in Airway Epithelial Cells

Mark J. Turnera,b Yukiko Satoa,b David Y. Thomasb,c Kathy Abbott-Bannerd John W. Hanrahana,b

aDepartment of Physiology, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada, bCystic Fibrosis Translational Research Centre, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada, cDepartment of Biochemistry, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada, dGlaxo-Smith-Kline, GSK House, Brentford, UK

Introduction

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a chloride and bicarbonate selective channel expressed at the apical membrane of epithelia in many tissues including the lungs, pancreas, intestine and sweat glands [1, 2]. Mutations in cftr cause the disease cystic fibrosis [3-5], which is characterized by reduced anion and fluid secretion and impaired airway immune defense that results in bacterial colonization, chronic inflammation and a gradual decline in pulmonary function [6]. CFTR is tightly regulated by the cAMP/PKA signalling pathway [7], hence components of this pathway have been proposed as therapeutic targets for the treatment of CF. cAMP signalling is terminated when the second messenger is hydrolysed by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs).

In humans, PDEs form a superfamily comprising 11 distinct isozymes (PDE1 – 11) and many splice variants, yielding ~100 enzymes [8, 9]. PDE4, 7 and 8 are specific for cAMP hydrolysis, PDE5, 6 and 9 hydrolyse cGMP only, and PDE1, 2, 3, 10 and 11 hydrolyse both cyclic nucleotides. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors have been studied for their ability to elevate intracellular cAMP ([cAMP]i) and activate CFTR in airway epithelia. PDE3 inhibitors elevate [cAMP]i and stimulate CFTR-dependent anion secretion by pig tracheal submucosal glands [10] and in the Calu-3 cell line [10-12], a widely used model for human submucosal gland serous cells [13]. PDE4 inhibitors also activate CFTR in Calu-3 cells [11, 14] and in well-differentiated primary human bronchial surface epithelial cells [15-17].

PDE4 inhibitors potentiate cAMP signaling, increasing CFTR-dependent anion and fluid secretion and production of airway surface liquid [18, 19]. In addition to regulating wild-type CFTR, they also augment isoproterenol-stimulated secretion by primary human bronchial epithelial cells (pHBE) from patients homozygous for the CFTR mutation F508del after partial rescue of the mutant by corrector drugs [17]. Previously, we showed that the dual PDE3/4 inhibitor ensifentrine (RPL554) enhances forskolin-stimulated CFTR activity in pHBEs with the F508del/R117H-5T genotype [16] as well as rare class III/IV CFTR mutants when they are expressed in FRT cells [20]. There is evidence that the cGMP-specific PDE5 also regulates CFTR in airway epithelia. An analogue of the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil was identified in a high throughput screen for correctors of F508del CFTR trafficking [21], and Lubamba, et

al. [22] found that PDE5 inhibitors stimulate CFTR-dependent Cl- transport across the nasal epithelium in F508del CF mice. Together these results suggest that inhibitors of specific PDE isozymes may have therapeutic value in CF and other diseases in which CFTR function is reduced, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD [23]). For a review of PDE inhibitors in CF see Turner, et al. [24].

In a recent survey of PDE expression in well differentiated pHBE cultures using qPCR we found relatively high levels of PDE8A mRNA [16]. Human PDE8A has 713 amino acids and a catalytic domain with 38.5% sequence identity to PDE4 [25]. It is most abundant in the testis, ovaries, small intestine and large intestine but has low expression in the lung and other tissues. Compared to PDE4, PDE8A has higher affinity for cAMP when determined in vitro (Km = 55-155 nM for PDE8A vs 2400 nM for PDE4), lower catalytic turnover (Vmax = 150 pmol min-1 µg-1 protein for PDE8A vs 2.2 nmol min-1 μg-1 protein PDE4) and lower sensitivity to the inhibitor IBMX [25]. It has been postulated to help maintain low basal cAMP levels and is implicated in Raf-1-MEK-ERK signalling [26, 27], cardiac contraction [28], cancer cell migration [29] and testosterone and progesterone steroidogenesis [30-32]. PDE8A was recently shown to downregulate cAMP following activation of β2-adrenergic receptors in human airway smooth muscle cells [33]. To our knowledge the role of PDE8 in airway epithelium has not been investigated.

Here, we show that PDE8A is functionally expressed in well-differentiated pHBE cells, and also at a lower level in the bronchial epithelial cell line CFBE41o-. Inhibition of PDE8A stimulates wild-type CFTR in pHBE cells and also increases the activity of mutant channels in F508del/F508del and F508del/R117H-5T HBE cells treated with CFTR modulators. The results identify PDE8 as a novel regulator of CFTR and potential therapeutic target for the treatment of CF.

Materials and Methods

BHK cells

Baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s MEM/F12 supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 U ml-1 penicillin and 100 μg ml-1 streptomycin. For overexpression studies, 5 x 105 cells were seeded onto Corning 6 well plates and incubated at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2 for 48 h. Cells were then transfected with 1 μg of human PDE8A in pCMV6-XL5 (Origene) using 3 μl Gene Juice (Novagen) in serum-free media. The transfection mix was removed 12 h later and replaced with complete medium for another 24 h before cells were studied.

CFBE41o- cells

We used a CFBE41o- human bronchial epithelial cell line (CFBE41o- WT) kindly provided by Eric Sorscher and Jeong Hong (Emory University School of Medicine) that had been transduced with lentiviral wild-type CFTR as described previously [34]. Cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Media (MEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FCS, 100 U ml-1 penicillin, 100 μg ml-1 streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine and maintained in T75 flasks (Corning) at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. For experiments, 80,000 cells were seeded on collagen coated 6.5 mm dia. Costar® 0.4 μm pore, polyester membrane inserts (Corning) and kept submerged for 24 h, then apical medium was removed and cells were maintained at the air-liquid interface for 1 week prior to study.

Primary human bronchial epithelial (pHBE) cell culture

Non-CF lung specimens were obtained from the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine (IIAM) and the National Disease Research Institute (NDRI), and cells were isolated by the Primary Airway Cell Biobank (PACB) at McGill University. F508del/R117H-5T cells were from the Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core at the UNC CF Center. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of McGill University (# A08-M70-14B). The methods for isolation, culture, and differentiation of pHBE cells were adapted from those described previously by Fulcher, et al. [35]. Briefly, cells were isolated by enzyme digestion and cultured in bronchial epithelial growth medium on type I collagen-coated plastic flasks (PureCol; Advanced BioMatrix), then trypsinized, counted, and cryopreserved. For experiments, cells were seeded on collagen coated 6.5 mm dia. Costar® 0.4 μm pore, polyester membrane inserts (Corning), and kept submerged for 4 days, then the apical medium was removed and the cells were allowed to differentiate at an air–liquid interface (ALI) for ≥ 21 days before study. The growth medium was complemented with penicillin, streptomycin and gentamycin antibiotics according to recent patient microbiology reports. In total, pHBE cells isolated from 11 different donors were studied of which 8 were male and the age range of donors was 31-69.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing

CFBE41o- WT cells were nucleofected with CRISPR sgRNA (pCLIP-Dual-SFFV-ZsGreen) and pCLIP-Cas9-hCMV-Blast from the transEDIT-dual library (TransOMIC Technologies) at the McGill Platform for Cellular Perturbation of the Goodman Cancer Research Centre and Department of Biochemistry at McGill University. After transfection, cells were cultured in CFBE41o- culture medium containing puromycin (4 µg ml-1) and blasticidin (10 µg ml-1) for cell selection. Expression of Cas9 was tested by qPCR and expression of sgRNA was assessed by confocal microscopy (data not shown). After a stable population of cells was acquired, they were sorted into single clones by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Single cell clones were cultured and the knockdown of PDE8A was assessed by qPCR.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted and purified using the Illustra™ RNAspin Mini RNA Isolation Kit (GE Healthcare) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For reverse transcription, 300 ng RNA was incubated with 5x All-In-One RT Mastermix (ABM) in a reaction volume of 20 μl for 10 min at 25°C, 15 min at 42°C and 5 min at 85°C. 0.5 µl cDNA, 10 μl of TaqMan® Fast Advanced Mastermix, 1 μl of TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay in a reaction volume of 20 μl was added to the wells of a MicroAmp® EnduraPlate™ Optical 96-Well Fast Reaction Plate. The qPCR was carried out using a QuantStudio™ 7 Flex Real-Time PCR system and the following protocol: 20 s at 95°C and 40 cycles at 95˚C (1 s) and 60°C (20 s). ΔΔCT analysis was performed using the manufacturer’s software package. The efficiency of each TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay used in this study was 95-105%.

Immunoblotting

pHBE cells, CFBE41o- WT cells or BHK cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 0.1% SDS (w/v), 1% Triton X-100 (w/v), 0.08% sodium deoxycholate (pH 8.0) and a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). For experiments that involve detection of phosphorylated proteins, RIPA buffer was supplemented with a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). 40 µg protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE before transferring to a nitrocellulose membrane. Rabbit anti-PDE8A (1:5000; Abcam; ab109597), rabbit anti Phospho-PKA substrate (1:1000; Cell Signalling Technology) rabbit anti-actin (1:2500; Abcam; ab8227) or mouse anti-tubulin (1:2000; Sigma) primary antibodies were added to the blot overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed with Tris Buffered Saline (TBS) + 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP were added at 1:10,000 dilution in TBS-T for 1 h. To detect HRP activity, equal volumes of Amersham™ ECL™ Western Blotting Reagents (GE Lifesciences) were added for 10 min before exposing the blot to Kodak Scientific Imaging film for 30 s and processing (Mini-Med/90, AFP Imaging) or developing the blot using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

Intracellular cAMP measurements using ELISA

24 h prior to study, pHBE or CFBE41o- WT cells were washed 3 x with PBS and cultured in serum- and antibiotic-free medium. Cells were then incubated in high Cl- saline solution, stimulated with pharmacological agonists, and incubated at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2 for 15 min prior to lysis with 0.1 M HCl. cAMP levels were determined using an intracellular cAMP ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Intracellular cAMP measurements using FLIM-FRET microscopy

The Epac-SH187 FRET construct was a gift from Dr Kees Jalink (Netherlands Cancer Institute). It encodes a high affinity Epac1 sensor flanked by a mTurquoise2 donor and tandem Venus acceptorcp173Venus-cp173Venus [36]. mTurquoise2-N1 was from Michael Davidson and Dorus Gadella (Addgene plasmid # 54843; http://n2t.net/addgene:54843 [37]). To target Epac-SH187 to the cell membrane, the first 13 amino acids of Lyn tyrosine protein kinase were added to the N terminus by Genscript Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Elevated cAMP concentration induces a conformational change in Epac1 and reduces FRET between the mTurquoise2 and Venus regions of the fusion protein, increasing the lifetime of mTurquoise2. One million CFBE41o- WT cells were transfected with 3 μg of the FRET constructs using an Amaxa™ 4D-Nucleofector™ System with the Amaxa™ P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector™ X Kit (program DC100) and seeded onto fibronectin-coated, 35 mm FluoroDish™ (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota FL) cell culture dishes. Experiments were performed 24-48 h post transfection. Fluorescence lifetime images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM-710-FLIM (PicoQuant, Berlin, Germany) microscope at x20 magnification and cells were excited using a 440 nm laser in pulse mode at 20 MHz. Photons were collected for 120 s using a time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) device coupled to the microscope and CFP bandpass emission filter (480 ± 20 nm). Lifetime measurements of mTurquoise2 were calculated by performing a double exponential, reconvolution fit of the TCSPC histogram, which generated the average lifetime using the following equation:

Lifetime = Σ Amplitude ∙ τ2 / Σ Amplitude ∙ τ

Short circuit current measurements

One day prior to study, pHBE or CFBE41o- WT cells were washed 3 x with PBS and cultured in serum- and antibiotic-free medium. Cells were mounted in modified Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) containing 5 ml saline, which was continuously gassed with 5% CO2/95% O2. Monolayers were clamped at 0 mV using a Multichannel Voltage-Current Clamp (Physiologic Instruments) and currents recorded using a Powerlab 8SP (AD Instruments, Dunedin, NZ) and analyzed using LabChart 7.0 software. Transepithelial resistance (Rte) was monitored by applying a 1 mV pulse (duration: 2 s) every 30 s and resistance calculated using Ohm’s Law. All drugs were added apically unless otherwise stated.

Solutions and reagents

CFTRinh-172 was kindly provided by R. Bridges, Rosalind Franklin Univ. of Medicine and Science, North Chicago IL, and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics. Ensifentrine was obtained from Verona Pharma (London, UK) and PF-04957325 was obtained from the Compound Transfer Program (Pfizer) and MedChem Express. Reagents for cell culture were purchased from Wisent unless otherwise stated, and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For Isc measurements, in non-permeabilized conditions, the basolateral saline solution contained (mM): 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, 2.4 KH2PO4, 1.24 K2HPO4, and 10 D-Glucose and the apical saline solution contained (mM): 1.2 NaCl, 115 Na-gluconate, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgCl2, 4 CaCl2, 2.4 KH2PO4, 1.24 K2HPO4, and 10 D-glucose; In permeabilized conditions, the basolateral saline solution contained (mM): 1.2 NaCl, 115 Na-gluconate, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgCl2, 4 CaCl2, 2.4 KH2PO4, 1.24 K2HPO4, and 10 D-glucose and the apical saline solution contained (in mM) 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, 2.4 KH2PO4, 1.24 K2HPO4, and 10 D-Mannitol. All solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 when gassed with 5% CO2/95% O2.

Statistical analysis

Data are displayed as mean ± S.D. unless otherwise stated. Sample sizes are displayed as n, the number of inserts and N, the number of donors or independent cell cultures where applicable. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA (with Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test) or two-way ANOVA (with Bonferroni post-test) were carried out with p < 0.05 considered significant. The coefficiency of drug interaction (CDI) was calculated as AB / (A×B), where AB represents the effect of both drugs together and A and B represent the effects of drug A and drug B when tested individually. A CDI of >1 indicates synergistic stimulation by drugs in combination [38].

Results

PDE8A is expressed in well-differentiated human airway epithelia

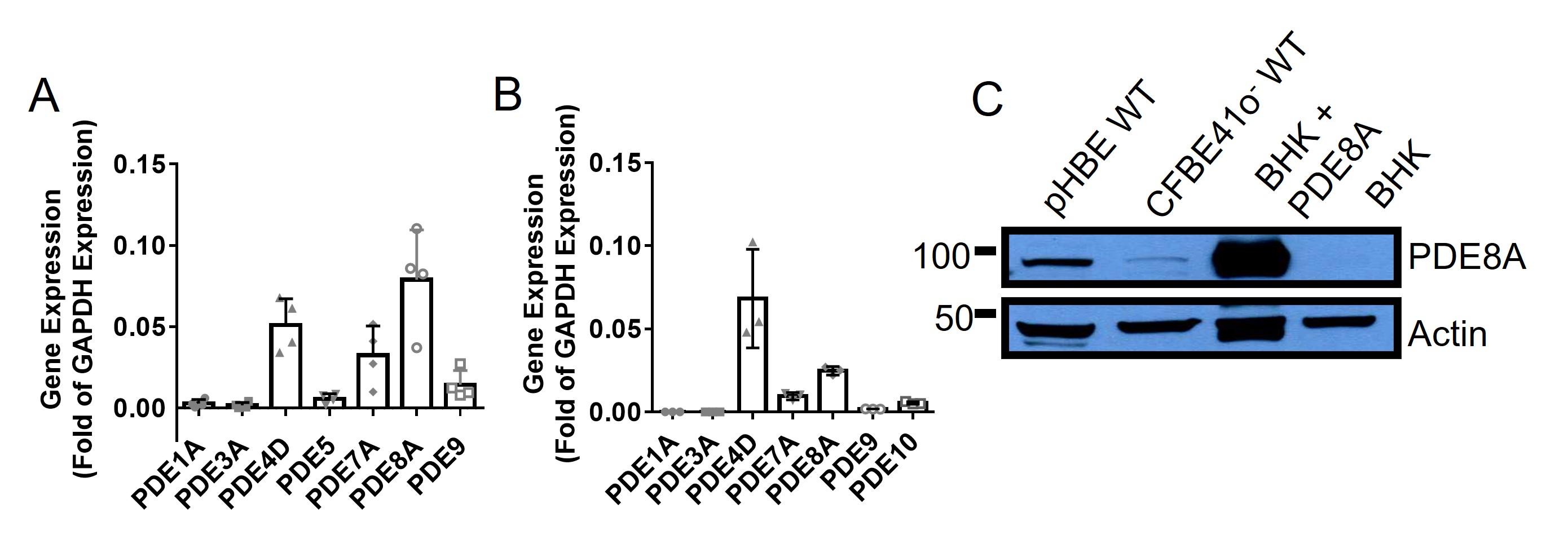

We began by assessing PDE8A expression using pHBE cells and comparing its level to that of 6 other PDEs for which there is evidence in airway epithelial cells [39-41]. High PDE8A mRNA expression was detected in pHBE cell lysates that was comparable to that for PDE4D, widely considered to be the main PDE regulating CFTR in HBE cells, after normalization to GAPDH (Fig. 1A). These results are consistent with our previous study of pHBE cell lysates from three different cell donors [16]. We also observed PDE8A mRNA in CFBE41o- cells that stably express wild-type CFTR (CFBE41o- WT), although levels were lower than in pHBE cells (Fig. 1B). We assessed PDE8A protein expression by immunoblotting and observed a band with the expected molecular mass in both pHBE and CFBE41o- WT cells, again with lower expression in the latter. No PDE8A was observed in control BHK cell lysates, however a strong band appeared when PDE8A was transiently overexpressed (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that PDE8A mRNA and protein are highly expressed in well-differentiated human airway epithelial cells and at a low level in the CFBE41o- cell line.

Inhibiting PDE8 in pHBE cells increases basal and forskolin-stimulated [cAMP]i

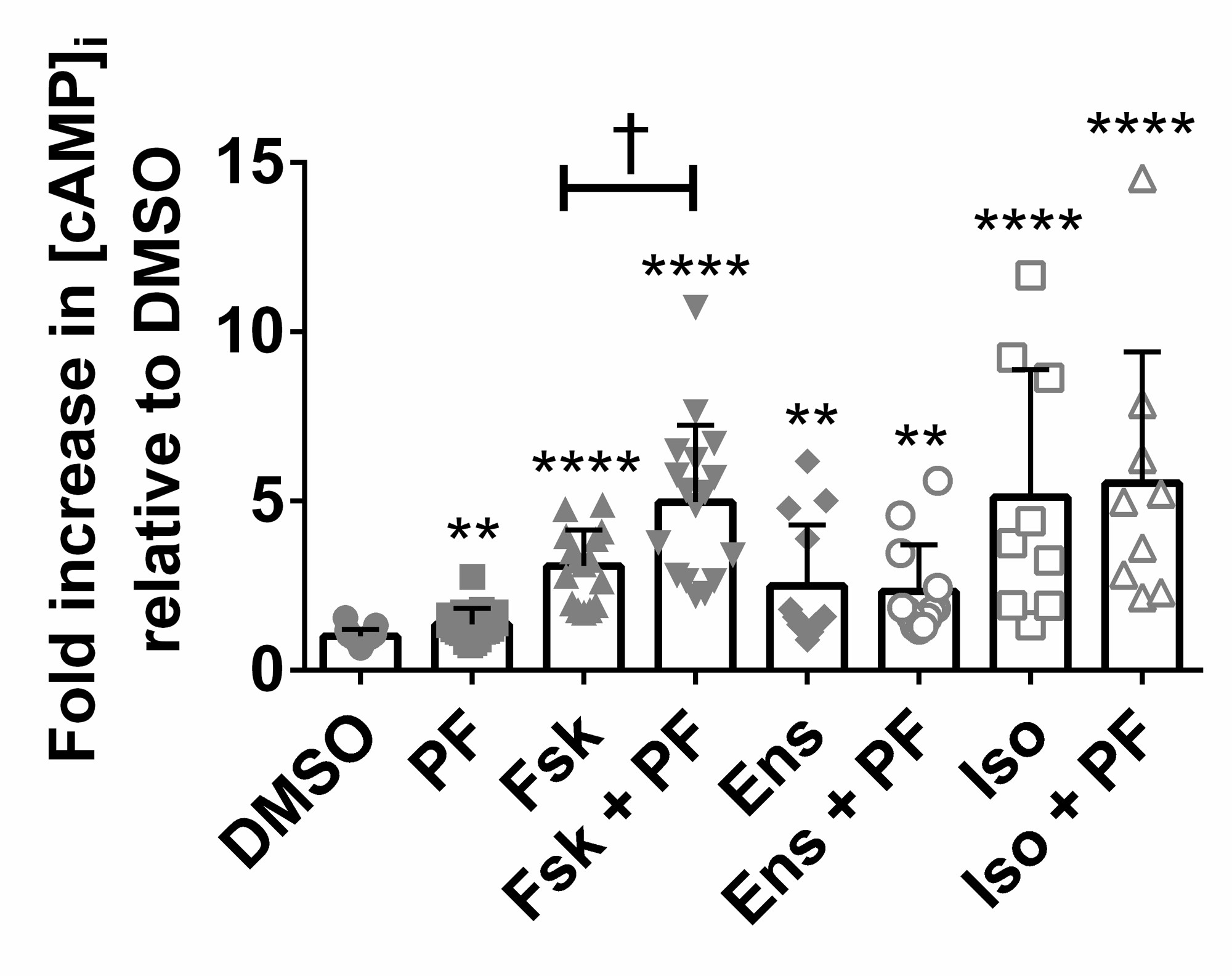

PDE8 is a high affinity, cAMP-specific PDE [25], therefore its inhibition is predicted to elevate [cAMP]i above basal levels. We used the PDE8 selective inhibitor PF-04957325 (PF) that has the following IC50’s in vitro: PDE8A = 0.0007 μM, PDE8B <0.0003 μM, and > 1.5 μM for all other PDEs tested [26]. Well-differentiated, non-CF pHBEs were treated for 15 min. This increased [cAMP]i 1.36 ± 0.11-fold compared to cells treated with vehicle (p < 0.01; n=19, N=4; Fig. 2) indicating that basal cAMP levels are regulated by PDE8. PF also enhanced forskolin-stimulated cAMP levels from 3.09 ± 0.27 to 4.97 ± 0.55 (p < 0.01; n=16, N=4; Fig. 2). The dual PDE3/4 inhibitor ensifentrine (Verona Pharma) and isoproterenol caused larger increases in [cAMP]i that were not further elevated by PF (Fig. 2). These results suggest that PDE8 regulates cAMP levels in pHBE cells.

Inhibiting PDE8 stimulates CFTR-dependent secretion by pHBE cells

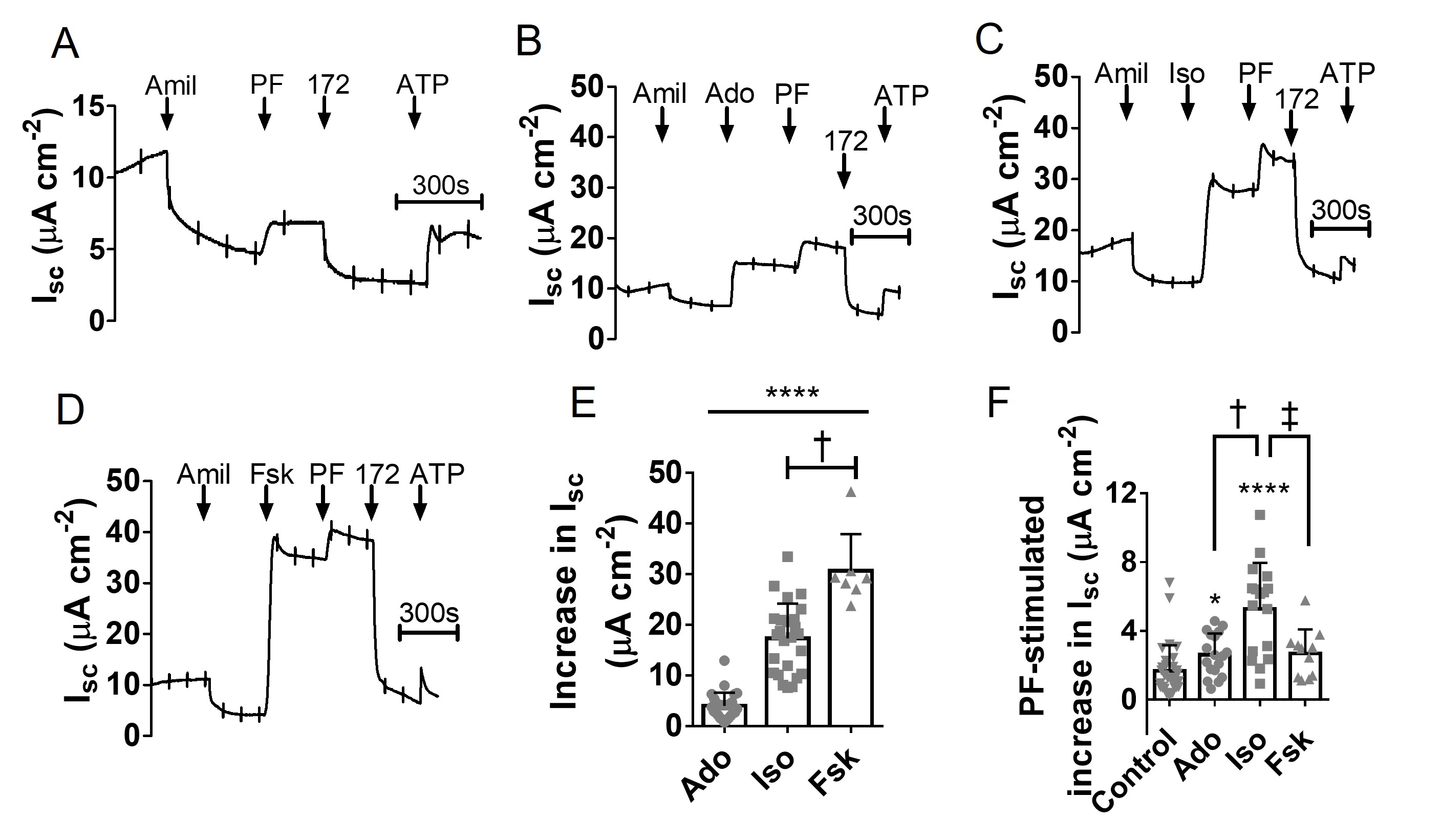

Having established that PDE8 inhibition modulates [cAMP]i in well-differentiated, non-CF pHBE cells, we next measured Isc responses to determine if PDE8 inhibition increases CFTR activity. Under basal conditions, PF increased the Isc by 1.67 ± 1.50 μA cm-2 (p < 0.0001 vs DMSO; n=31; N=7) and this response was abolished by the CFTR channel inhibitor CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 3A). We then compared the Isc response to PDE8 inhibition after cells had been pre-treated with forskolin, isoproterenol or adenosine (Fig. 3B-3D). These cAMP elevating agents caused Isc increases in the rank order forskolin > isoproterenol > adenosine (Fig. 3E). Adding PF after these agents further enhanced Isc by 2.68 ± 0.43 μA cm-2, 5.29 ± 0.65 μA cm-2 and 2.61 ± 0.34 μA cm-2, respectively (n = 11-18, N=3-4; Fig. 3F). The increase with PF was larger during stimulation by isoproterenol than in unstimulated cells, or in cells exposed to forskolin or adenosine (p<0.01; Fig. 3F). These results demonstrate that inhibiting PDE8 stimulates CFTR under both basal and stimulated conditions and is most effective for the β2-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol.

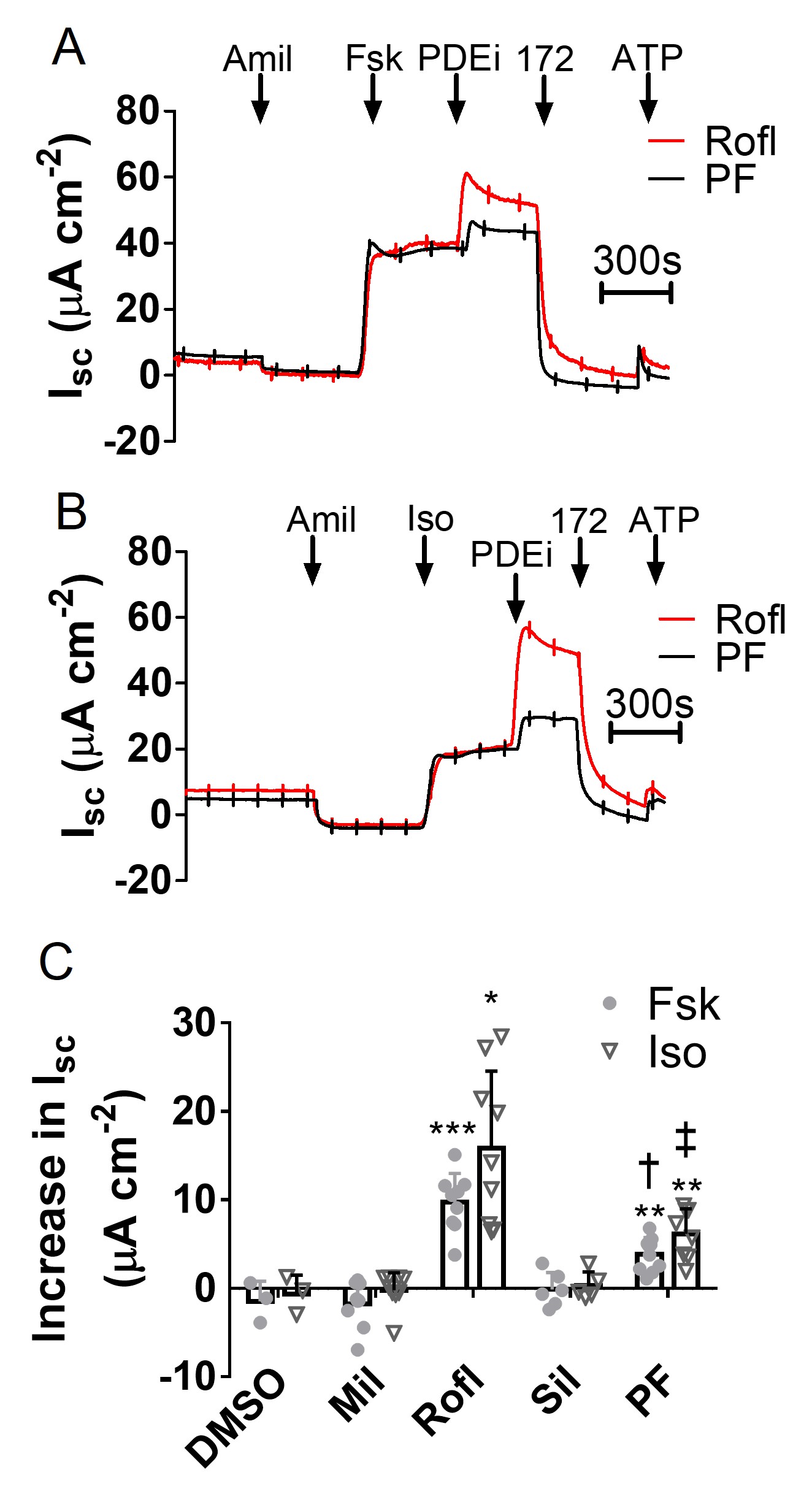

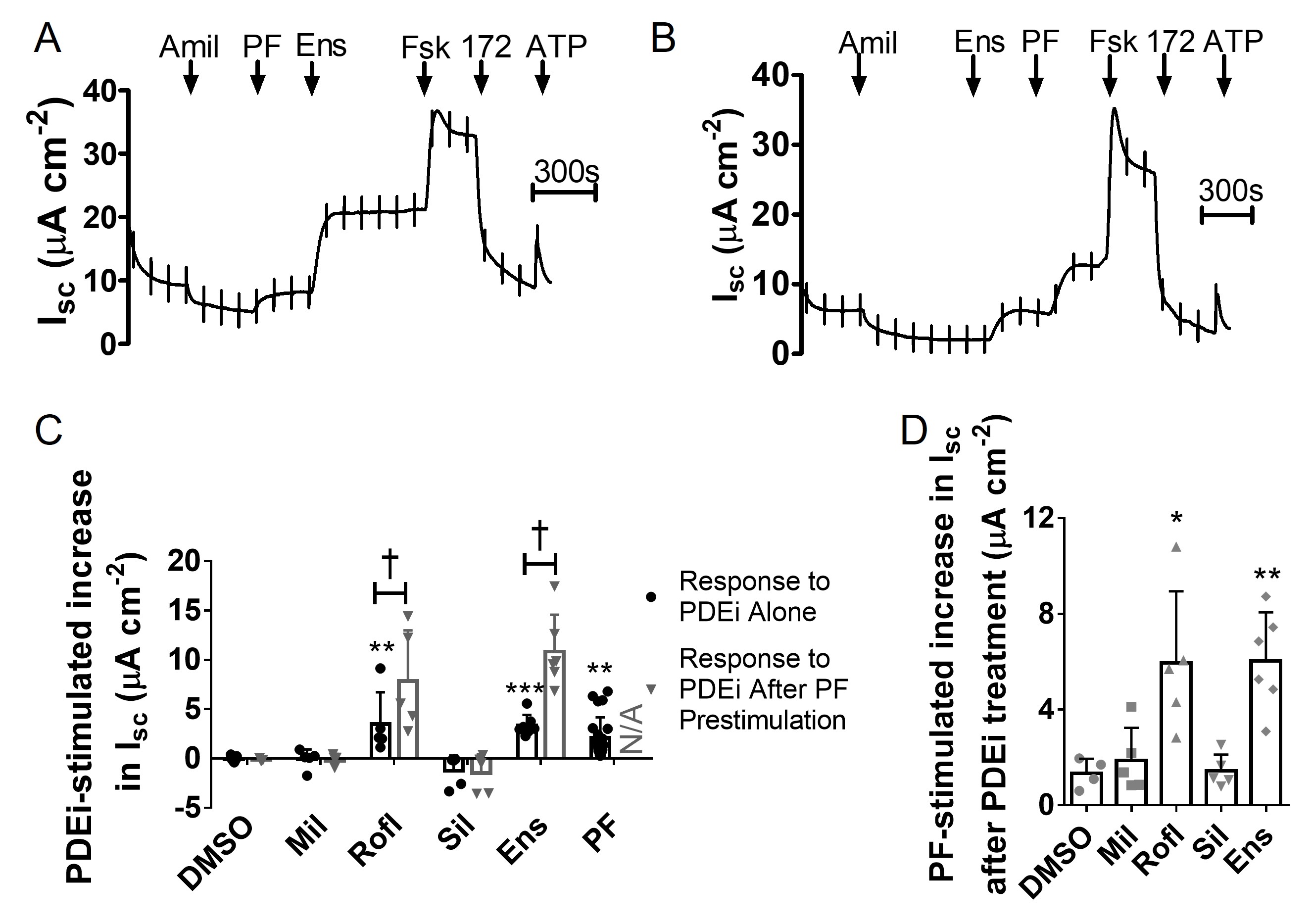

We compared responses to PF to other PDE inhibitors in human airway epithelium after pre-stimulation by forskolin or isoproterenol. Neither milrinone (PDE3 inhibitor) nor sildenafil (PDE5 inhibitor) further increased stimulation by forskolin or isoproterenol (Fig. 4), whereas roflumilast (PDE4 inhibitor) increased forskolin and isoproterenol-stimulated Isc by 9.72 ± 1.09 μA cm-2 (n=9, N=3) and 15.85 ± 2.90 μA cm-2 (n=9, N=3), respectively (Fig. 4C). Roflumilast was more effective than PF in stimulating CFTR-dependent Isc, confirming PDE4 as the predominant PDE that regulates CFTR in well differentiated pHBE cells. However, the data indicate that PDE8 also has an important functional role.

Inhibiting PDE8 enhances the CFTR response to PDE4 inhibitors and vice versa

We next compared the effects of PDE inhibitors individually and in combination under basal conditions. Without prestimulation, neither milrinone nor sildenafil stimulated Isc across well-differentiated pHBE cells whereas PF, roflumilast and ensifentrine all generated small, but significant increases in Isc (Fig. 5A and 5B). This implies that PDE4 and PDE8 inhibitors may cause similar elevation of basal cAMP levels in pHBE cells (Fig. 5C). Pretreating cells with PF enhanced roflumilast and ensifentrine stimulation of Isc by 2.25 ± 1.13 fold (p < 0.05; n = 5, N = 2; Fig. 5C) and 3.83 ± 0.83 fold, respectively (p < 0.05; n = 6-9, N = 2, Fig. 5C) but did not affect milrinone- and sildenafil-stimulated currents. Conversely, pretreating cells with roflumilast or ensifentrine increased the PF response by 4.43 ± 1.41 fold (p < 0.05; n=5, N=2; Fig. 5D) and 4.50 ± 1.18 fold (p < 0.01; n = 6, N = 2; Fig. 5D), respectively, but did not alter responses to milrinone or sildenafil. The calculated coefficiency of drug interaction (CDI) was greater than 1, indicating that PDE4 and PDE8 inhibitor effects on CFTR activity are synergistic when used in combination.

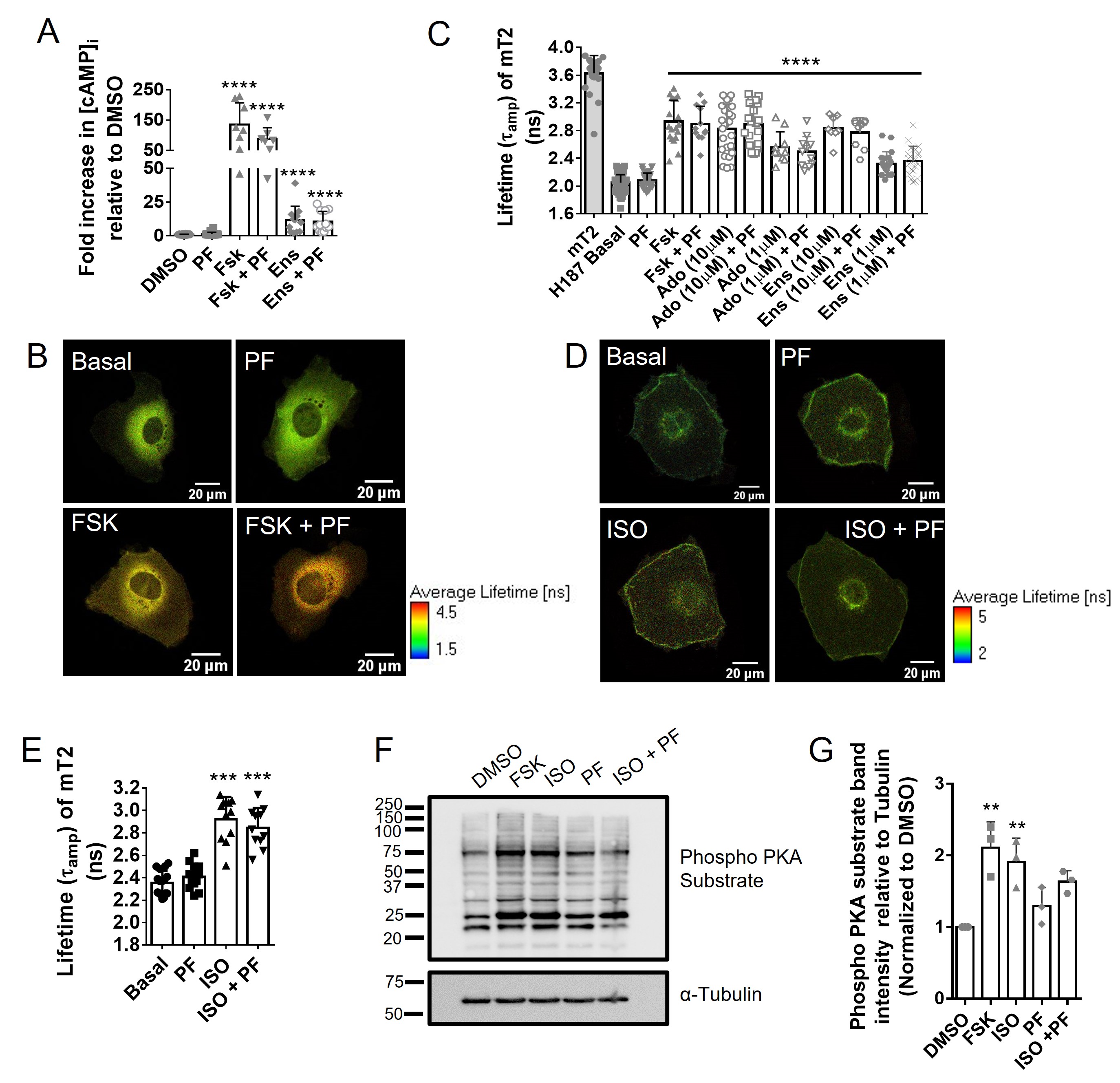

PDE8 inhibition does not cause a measurable increase in global [cAMP]i in CFBE41o- WT cells

Having shown that PDE8 regulates CFTR in pHBE cells, we next used polarized CFBE41o- WT cells as a model to further explore PDE8-dependent regulation of CFTR given that they express PDE8A mRNA and protein, albeit at lower levels than pHBE cells (see Fig. 1). Measurements of [cAMP]i using ELISA showed that PF did not elevate total [cAMP]i above that of DMSO-treated cells (fold increase = 1.45 ± 0.28; p > 0.05 vs DMSO; n = 20, N = 5; Fig. 6A). Forskolin and ensifentrine both increased [cAMP]i compared to DMSO-treated cells (fold increase = 134.9 ± 25.39 and 11.67 ± 2.97 respectively; p < 0.001 vs. DMSO; n = 7-12; N = 3), however there was no further increase when either treatment was combined with PF (Fig. 6A). We also measured [cAMP]i in CFBE41o- WT cells using Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) with the high affinity Exchange protein activated by cAMP (EPAC)-based Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensor EPAC-SH187, which consists of EPAC flanked by the donor mTurquoise 2 and the tandem repeat acceptor Venus [36]. With this probe, increased [cAMP]i is detected by measuring the fluorescence lifetime of the FRET donor mTurquoise2 as a readout for reduced FRET. Fig. 6B shows typical images collected during experiments. Fig. 6C summarizes the effect of cAMP agonists on mTurquoise2 lifetime. PF did not change the fluorescence lifetime of mTurquoise2 when compared with untreated cells (2.08 ± 0.02 ns vs 2.05 ± 0.01 ns; n=31-88, N = 5-7; p>0.05) indicating [cAMP]i was not increased, in contrast to forskolin, adenosine and ensifentrine, which induced significant increases in [cAMP]i that were not further enhanced by PF. FRET-FLIM measurements were also made in cells using a modified EPAC-SH187 that was targeted to the membrane by N-terminal fusion of a Lyn tyrosine kinase sequence. However, targeting the FRET-FLIM sensor to the plasma membrane did not produce measurable PF-induced changes in the fluorescence lifetime of mTurquoise2 in control or isoproterenol-stimulated cells (Fig. 6D-6E). These results indicate that any increases in cAMP due to PF are below the detection threshold for the FRET sensor. As an alternative method for detecting of cAMP/PKA signalling, we tested whether PKA-dependent protein phosphorylation is broadly increased by PDE8 inhibition by probing immunoblots using an antibody that detects phosphorylated serine and threonine residues with arginine at the -3 and -2 positions (RRXS*/T*) as occurs in dibasic consensus PKA sites. A representative immunoblot is shown in Fig. 6F. Densitometry confirmed that forskolin and isoproterenol both caused significant phosphorylation of PKA substrates whereas PF did not (Fig. 6G). These data are consistent with the ELISA experiments and confirm that PF does not cause a detectable increase in global [cAMP]i in CFBE41o- WT cells.

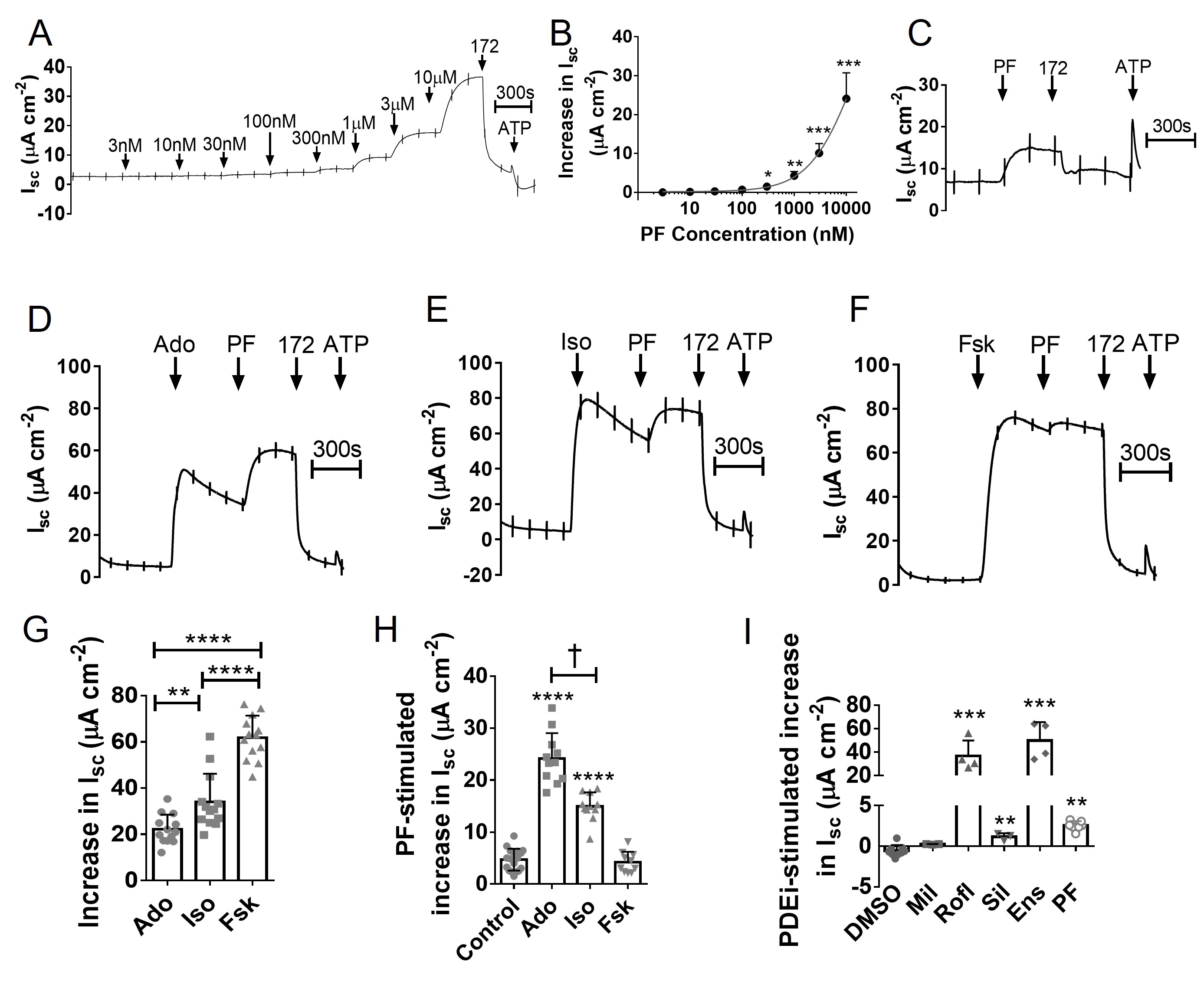

Inhibiting PDE8 stimulates CFTR-dependent Isc in CFBE41o- WT cells

Although PF did not increase [cAMP]i measurably in CFBE41o- WT cells, CFTR activation was detectable at 300 nM PF and was further increased at higher concentrations (Fig. 7A and 7B). At 500 nM, the PF stimulation was highly significant (4.69 ± 0.50 μA cm-2; n = 18; N = 5; p < 0.001 vs. DMSO) and sensitive to CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 7C). We next assessed the effect of inhibiting PDE8 in cells pre-stimulated with forskolin, isoproterenol or adenosine (Fig. 7D-7F). Forskolin caused the largest increase in Isc (61.84 ± 2.63 μA cm-2; n = 13, N = 3) followed by isoproterenol (34.04 ± 3.38 μA cm-2; n = 13, N = 3) and adenosine (22.18 ± 1.76 μA cm-2; n = 13, N = 3), similar to results with well-differentiated pHBE cells (compare summary in Fig. 7G with Fig. 3E). PF responses were inversely proportional to the prestimulation; i.e. acute PF responses were largest after adenosine, intermediate after isoproterenol, and smallest after forskolin (Fig. 7H). We also compared the effects of different PDE inhibitors on unstimulated CFBE41o- WT cells. Milrinone had no effect whereas roflimulast and ensifentrine both produced robust CFTR-dependent currents that were larger than those elicited by sildenafil and PF (Fig. 7I). These results indicate there is substantial cAMP production in CFBE41o- WT cells under control conditions which is mostly degraded by PDE4.

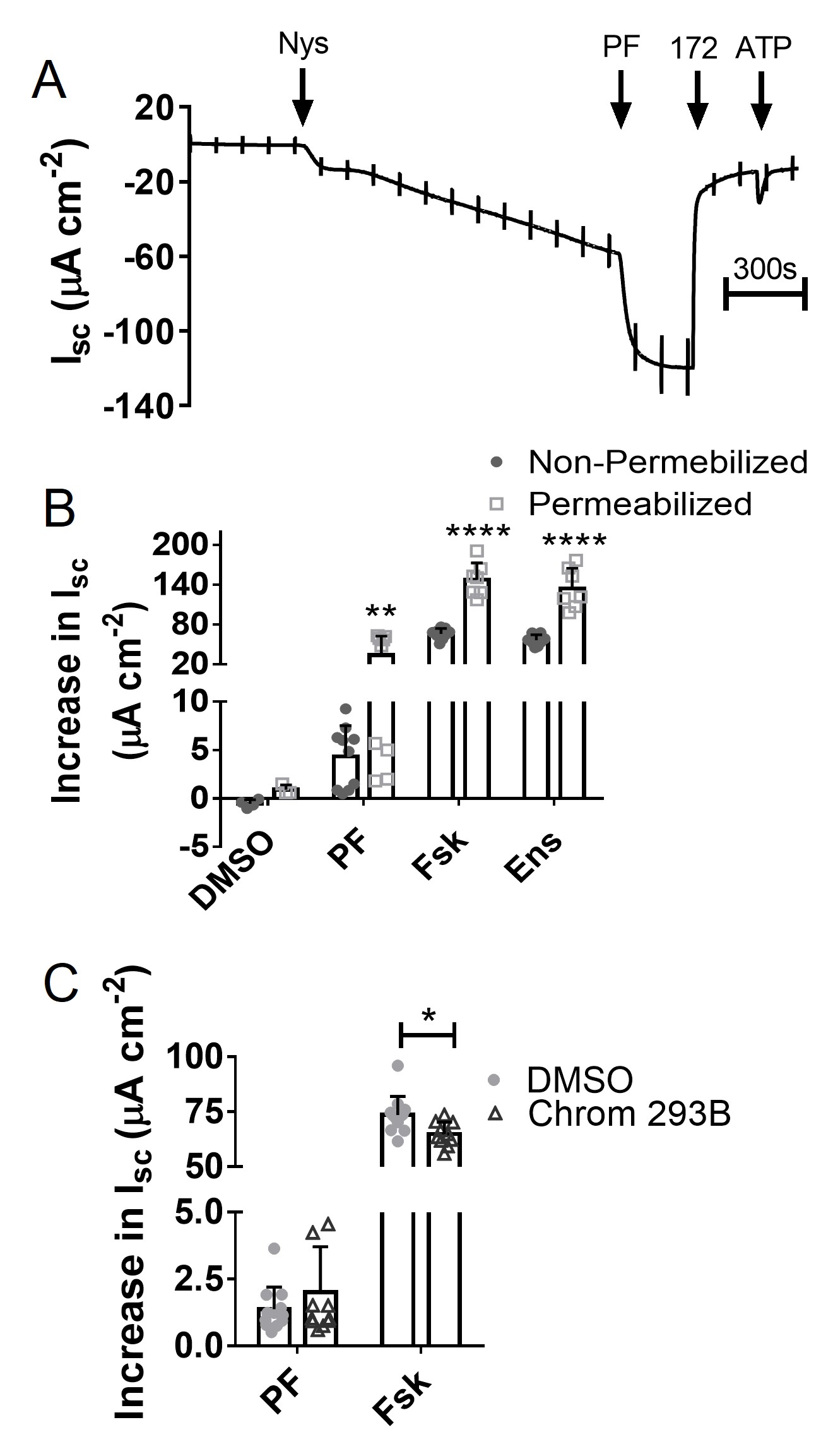

PDE8 inhibition increases Isc by direct activation of CFTR at the apical membrane

The functional responses in CFBE41o- WT made it possible to localize the effects of PF. We measured Isc while permeabilizing the basolateral membrane in the presence of a reversed transepithelial Cl- gradient (i.e. from basolateral-to-apical to apical-to-basolateral to minimize cell swelling). Nystatin produced a negative Isc of 25.78 ± 3.78µA cm-2 (p<0.001 vs. control; n = 24; N=4), as expected when transepithelial Cl- flux is rate-limited by the conductance of the apical membrane (Fig. 8A). PF stimulated an Isc of 33.72 ± 9.62 µA cm-2 (n = 3-9; N=3; Fig. 8B) demonstrating that it acts at the apical membrane. Basolateral permeabilization increased the response to PF more than to forskolin or ensifentrine suggesting those treatments may normally raise [cAMP]i sufficiently to activate basolateral K+ channels [42, 43]. In support of this interpretation, pre-treating unpermeabilized cells with the KCNQ1 inhibitor Chromanol 293B caused a small decrease in forskolin-stimulated Isc but had no effect on the response to PF (Fig. 8C). Together, these data demonstrate that PDE8 inhibition causes a localized activation of CFTR at the apical membrane of airway epithelia.

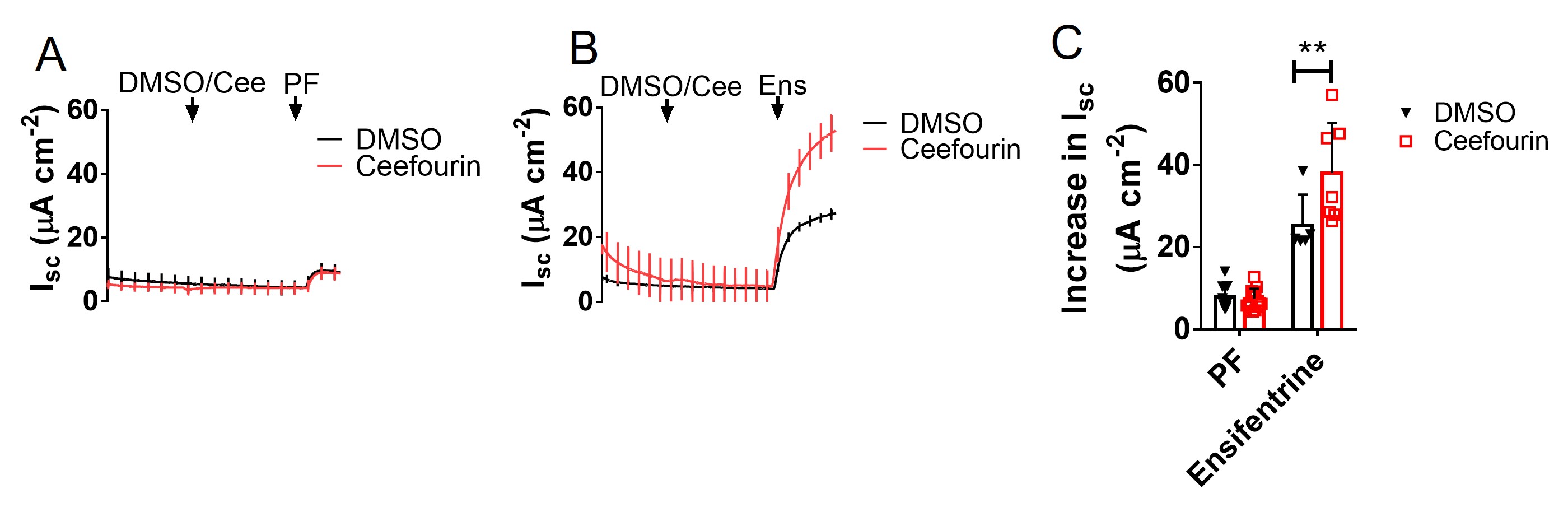

MRP4 influences PDE4- but not PDE8-regulated cAMP signalling

Several multidrug resistance proteins export cyclic nucleotides and one of these, MRP4, was implicated in the regulation of CFTR in the intestine when Mrp4 knockout mouse were found to have increased susceptibility to cAMP-induced secretory diarrhoea [44]. To examine the impact of MRP4 on Isc responses to PDE inhibitors, CFBE41o- WT cells were treated sequentially with vehicle or the MRP4 inhibitor ceefourin1 (20 µM [45]) followed by PF (500 nM) or ensifentrine (1 µM) (Fig. 9A, B). Ceefourin1 alone did not increase basal Isc, suggesting there is little if any MRP4-dependent cAMP efflux under control conditions (Fig. 9A, B). The response to PF was also unaffected by ceefourin1 whereas stimulation by ensifentrine was increased >50% (Fig. 9C). These results show that MRP4 modulation of functional responses to cAMP e.g. CFTR-dependent Isc, depends on the PDE inhibitor used and does not suppress the response to PF.

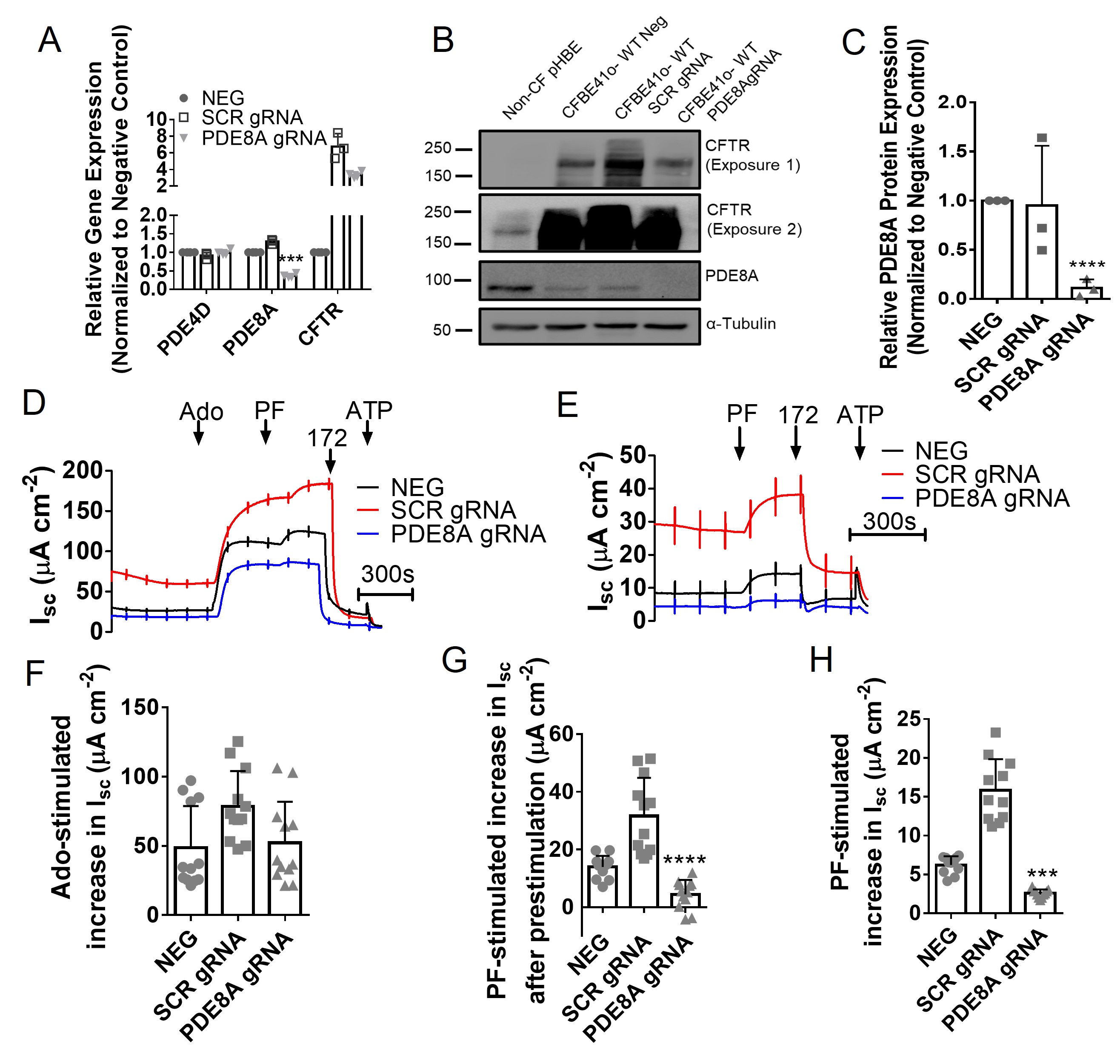

PDE8A knockdown using CRISPR Cas9 reduces PF stimulation of CFTR

If the stimulation by PF results from inhibition of PDE8A, it should be reduced by knockdown of PDE8A expression. To test this prediction, CFBE41o- WT cells were cotransfected with CRISPR gRNA targeting PDE8A and Cas9 as described in the Methods and clones were selected. One clone had a 64 ± 3% reduction in PDE8A mRNA according to qPCR (Fig. 10A) and 89 ± 5% reduction in protein expression in immunoblot when compared to the negative control (p < 0.0001; N = 3; Fig. 10A-10C). PDE8A knockdown strongly inhibited the Isc response to PF under both basal and adenosine-stimulated conditions (Fig. 10D-10H), supporting the conclusion that PF effects are mediated by inhibition of PDE8A. CFTR expression was increased by CRISPR gene editing in both scrambled control and PDE8A knockdown cells (see Fig. 10A-10B). This unexpected off-target effect strengthens the conclusion that PDE8A mediates the effects of PF on Isc since responses were reduced relative to negative and scrambled controls despite increased CFTR expression.

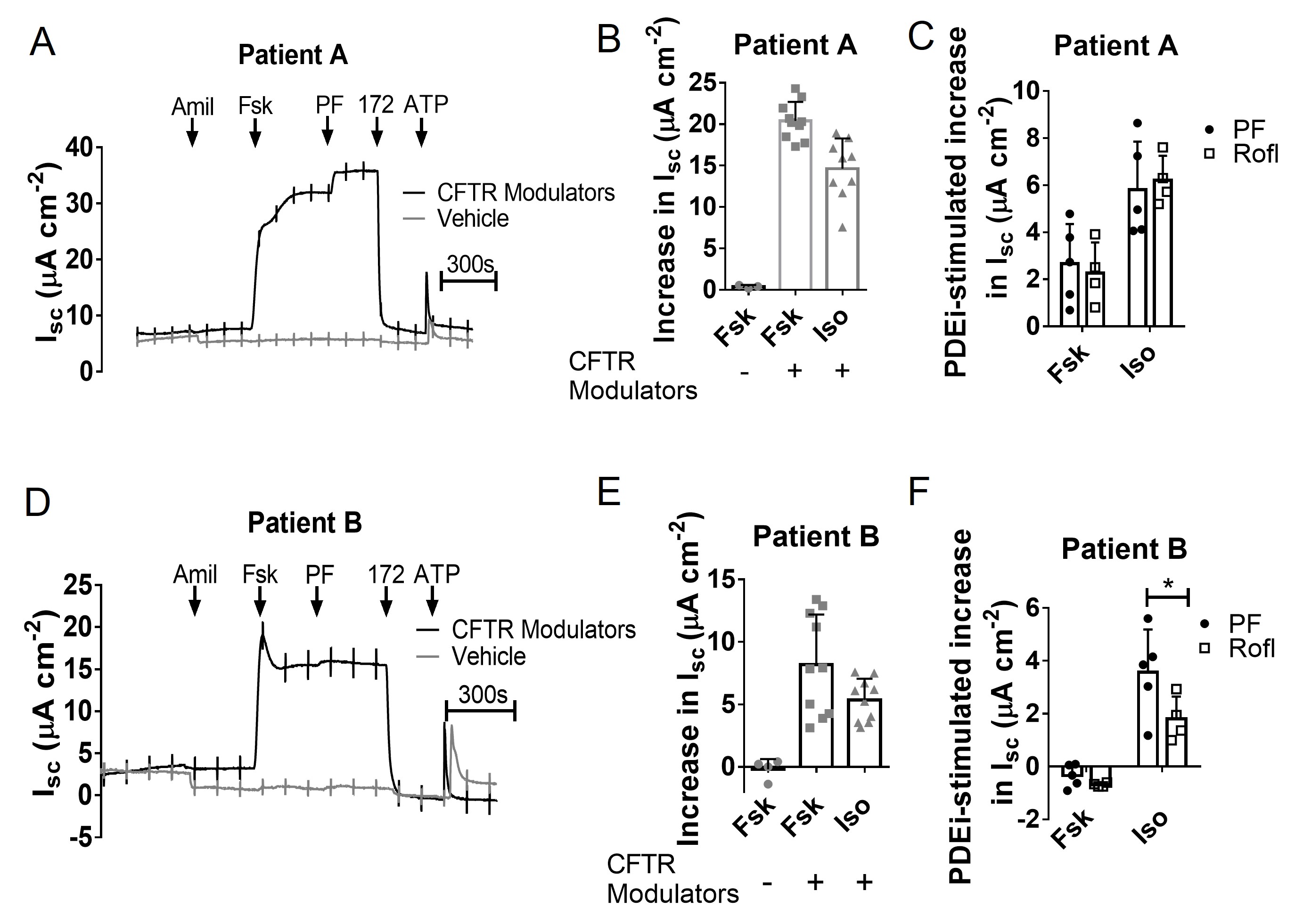

PDE8A inhibition increases activation of rescued F508del/F508del CFTR in pHBE cells

Having shown that PDE8A regulates wild-type CFTR in both pHBE and CFBE41o- cells, we next examined the efficacy of PDE8A inhibition after partial rescue of mutated CFTR using clinically approved modulators. Well-differentiated pHBE cells from two F508del homozygous patients were treated with vehicle or the modulators VX-445 + VX-661 + VX-770 for 24 h to mimic the clinically approved drug Trikafta™ [46, 47]. Forskolin and isoproterenol did not alter Isc when cells were pre-treated with vehicle but did cause stimulation when cells were pretreated with CFTR modulators, consistent with partial rescue of F508del CFTR (Fig. 11A, B, D, E). For patient A, PF enhanced forskolin- and isoproterenol-stimulated Isc responses to the same level as roflumilast and both PDE inhibitors had more pronounced effects after stimulation by isoproterenol compared to forskolin (Fig. 11C). CFTR modulators were less efficacious in cells from patient B, and neither PF nor roflumilast enhanced forskolin-stimulated Isc (Fig. 11D). Surprisingly, the increase in isoproterenol-stimulated Isc was larger with PF than with roflumilast despite roflumilast inducing larger effects in non-CF cells (Fig. 4). These results confirm the variation between individuals in responsiveness to corrector drugs [48] and indicate that PDE8A inhibitors may be beneficial for the treatment of F508del/F508del patients when combined with CFTR modulators.

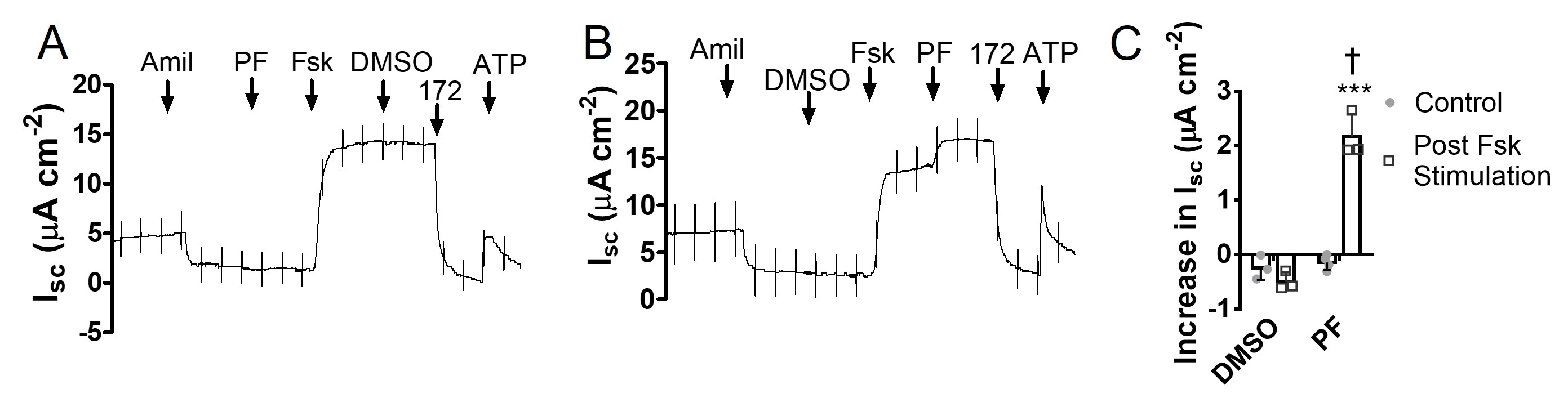

PDE8A inhibition stimulates CFTR activity in F508del/R117H-5T pHBE cells

In previous studies we showed that ensifentrine increases the activity of CFTR class III (gating) and class IV (permeation) mutants in Fisher rat thyroid cells and the class IV mutant R117H endogenously expressed in pHBE cells [16, 20]. To examine the effect of PDE8 inhibition on R117H CFTR, pHBE cells from a CF patient with the genotype F508del/R117H-5T were differentiated at the air-liquid interface, treated with the CFTR modulators VX-809 and VX-770 for 24 h, and then studied in Ussing Chambers (Fig. 12A-B). F508del/R117H-5T cells did not respond to PF alone (Isc increase: -0.15 ± 0.07 μA cm-2; p > 0.05 vs. DMSO; n = 4, N = 1; Fig. 12C); however, PF did increase Isc by 2.17 ± 0.24 μA cm-2 in F508del/R117H-5T cells that had been pretreated with forskolin (p < 0.001 vs. DMSO; n = 3, N = 1; Fig. 12C). These results demonstrate that PDE8A inhibition enhances the activation of mutant CFTR (F508del/R117H-5T) after partial rescue by CFTR modulators, encouraging development of PDE8A inhibitors as an adjunct therapy for CF.

We thank the Biobank of respiratory tissues at the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and Institut de recherche cliniques de Montréal, and Julie Goepp, Carolina Martini and Jessica de la Torre of the CF Canada Primary Airway Cell Biobank at McGill CFTRc for cell isolation and primary culture. We also thank Dr. Scott H. Randell at the University of North Carolina for providing pHBE F508del/R117H-5T cells. In addition, we extend our thanks to the Advanced Bioimaging Facility at McGill University for technical input for the FLIM-FRET studies. FACS was performed in the Flow Cytometry Core Facility of the Life Science Complex, McGill University and supported by funding from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation.

Author Contributions

M.J.T. conceived the study, designed experiments, acquired, analysed and interpretated data and drafted the manuscript. Y.S. acquired, analysed and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript. D.Y.T, K.A-B. and J.W.H. critically revised and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a fellowship awarded to M.J.T. from Verona Pharma plc with support from the UK CF Trust, and grants from Verona Pharma plc and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to JWH and DYT.

Statement of Ethics

Human lung tissue was obtained under protocols approved by Institutional Review Boards at McGill University (# A08-M70-14B) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Partial support for this research was provided by Verona Pharma and KAB was an employee of Verona Pharma plc when the study was undertaken. Verona Pharma plc and Pfizer Inc. did not influence the design of the experiments or interpretation of the results.

| 1 Riordan JR: CFTR function and prospects for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem 2008;77:701-726. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142532 |

||||

| 2 Csanady L, Vergani P, Gadsby DC: Structure, gating, and regulation of the CFTR anion channel. Physiol Rev 2019;99:707-738. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00007.2018 |

||||

| 3 Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, Drumm ML, Iannuzzi MC, Collins FS, Tsui LC: Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 1989;245:1066-1073. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2475911 |

||||

| 4 Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N, Zsiga M, Buchwald M, Tsui LC, Riordan JR, Collins FS: Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science 1989;245:1059-1065. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2772657 |

||||

| 5 Kerem B-S, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui LC: Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: Genetic analysis. Science 1989;245:1073-1080. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2570460 |

||||

| 6 Ratjen F, Bell SC, Rowe SM, Goss CH, Quittner AL, Bush A: Cystic fibrosis. Nature reviews Disease primers 2015;1:15010. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.10 |

||||

| 7 Dahan D, Evagelidis A, Hanrahan JW, Hinkson DA, Jia Y, Luo J, Zhu T: Regulation of the CFTR channel by phosphorylation. Pflugers Arch 2001;443:S92-96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004240100652 |

||||

| 8 Maurice DH, Ke H, Ahmad F, Wang Y, Chung J, Manganiello VC: Advances in targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2014;13:290-314. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4228 |

||||

| 9 Conti M, Mika D, Richter W: Cyclic AMP compartments and signaling specificity: role of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. J Gen Physiol 2014;143:29-38. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.201311083 |

||||

| 10 Penmatsa H, Zhang W, Yarlagadda S, Li C, Conoley VG, Yue J, Bahouth SW, Buddington RK, Zhang G, Nelson DJ, Sonecha MD, Manganiello V, Wine JJ, Naren AP: Compartmentalized cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate at the plasma membrane clusters PDE3A and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator into microdomains. Mol Biol Cell 2010;21:1097-1110. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.e09-08-0655 |

||||

| 11 Cobb BR, Fan L, Kovacs TE, Sorscher EJ, Clancy JP: Adenosine receptors and phosphodiesterase inhibitors stimulate Cl- secretion in Calu-3 cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:410-418. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2002-0247OC |

||||

| 12 Kelley TJ, al-Nakkash L, Drumm ML: CFTR-mediated chloride permeability is regulated by type III phosphodiesterases in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1995;13:657-664. https://doi.org/10.1165/ajrcmb.13.6.7576703 |

||||

| 13 Shen BQ, Finkbeiner WE, Wine JJ, Mrsny RJ, Widdicombe JH: Calu-3: a human airway epithelial cell line that shows cAMP-dependent Cl- secretion. Am J Physiol 1994;266:L493-501. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.5.L493 |

||||

| 14 Barnes AP, Livera G, Huang P, Sun C, O'Neal WK, Conti M, Stutts MJ, Milgram SL: Phosphodiesterase 4D forms a cAMP diffusion barrier at the apical membrane of the airway epithelium. J Biol Chem 2005;280:7997-8003. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M407521200 |

||||

| 15 Lambert JA, Raju SV, Tang LP, McNicholas CM, Li Y, Courville CA, Farris RF, Coricor GE, Smoot LH, Mazur MM, Dransfield MT, Bolger GB, Rowe SM: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activation by roflumilast contributes to therapeutic benefit in chronic bronchitis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014;50:549-558. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2013-0228OC |

||||

| 16 Turner MJ, Matthes E, Billet A, Ferguson AJ, Thomas DY, Randell SH, Ostrowski LE, Abbott-Banner K, Hanrahan JW: The dual phosphodiesterase 3 and 4 inhibitor RPL554 stimulates CFTR and ciliary beating in primary cultures of bronchial epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016;310:L59-70. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00324.2015 |

||||

| 17 Blanchard E, Zlock L, Lao A, Mika D, Namkung W, Xie M, Scheitrum C, Gruenert DC, Verkman AS, Finkbeiner WE, Conti M, Richter W: Anchored PDE4 regulates chloride conductance in wild-type and DeltaF508-CFTR human airway epithelia. FASEB J 2014;28:791-801. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-240861 |

||||

| 18 Schmid A, Baumlin N, Ivonnet P, Dennis JS, Campos M, Krick S, Salathe M: Roflumilast partially reverses smoke-induced mucociliary dysfunction. Respir Res 2015;16:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0294-3 |

||||

| 19 Tyrrell J, Qian X, Freire J, Tarran R: Roflumilast combined with adenosine increases mucosal hydration in human airway epithelial cultures after cigarette smoke exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015;308:L1068-1077. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00395.2014 |

||||

| 20 Turner MJ, Luo Y, Thomas DY, Hanrahan JW: The dual phosphodiesterase 3/4 inhibitor RPL554 stimulates rare class III and IV CFTR mutants. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2020;318:L908-L920. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00285.2019 |

||||

| 21 Robert R, Carlile GW, Pavel C, Liu N, Anjos SM, Liao J, Luo Y, Zhang D, Thomas DY, Hanrahan JW: Structural analog of sildenafil identified as a novel corrector of the F508del-CFTR trafficking defect. Mol Pharmacol 2008;73:478-489. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.107.040725 |

||||

| 22 Lubamba B, Lebacq J, Reychler G, Marbaix E, Wallemacq P, Lebecque P, Leal T: Inhaled phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors restore chloride transport in cystic fibrosis mice. Eur Respir J 2011;37:72-78. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00013510 |

||||

| 23 Rab A, Rowe SM, Raju SV, Bebok Z, Matalon S, Collawn JF: Cigarette smoke and CFTR: implications in the pathogenesis of COPD. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2013;305:L530-541. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00039.2013 |

||||

| 24 Turner MJ, Abbott-Banner K, Thomas DY, Hanrahan JW: Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibitors as therapeutic interventions for cystic fibrosis. Pharmacol Ther 2021;224:107826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107826 |

||||

| 25 Fisher DA, Smith JF, Pillar JS, St Denis SH, Cheng JB: Isolation and characterization of PDE8A, a novel human cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998;246:570-577. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.8684 |

||||

| 26 Vang AG, Ben-Sasson SZ, Dong H, Kream B, DeNinno MP, Claffey MM, Housley W, Clark RB, Epstein PM, Brocke S: PDE8 regulates rapid Teff cell adhesion and proliferation independent of ICER. PLoS One 2010;5:e12011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012011 |

||||

| 27 Basole CP, Nguyen RK, Lamothe K, Vang A, Clark R, Baillie GS, Epstein PM, Brocke S: PDE8 controls CD4(+) T cell motility through the PDE8A-Raf-1 kinase signaling complex. Cell Signal 2017;40:62-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.08.007 |

||||

| 28 Patrucco E, Albergine MS, Santana LF, Beavo JA: Phosphodiesterase 8A (PDE8A) regulates excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2010;49:330-333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.016 |

||||

| 29 Dong H, Claffey KP, Brocke S, Epstein PM: Inhibition of breast cancer cell migration by activation of cAMP signaling. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;152:17-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3445-9 |

||||

| 30 Lounas A, Vernoux N, Germain M, Tremblay ME, Richard FJ: Mitochondrial sub-cellular localization of cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase 8A in ovarian follicular cells. Sci Rep 2019;9:12493. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48886-8 |

||||

| 31 Shimizu-Albergine M, Tsai LC, Patrucco E, Beavo JA: cAMP-specific phosphodiesterases 8A and 8B, essential regulators of Leydig cell steroidogenesis. Mol Pharmacol 2012;81:556-566. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.111.076125 |

||||

| 32 Vasta V, Shimizu-Albergine M, Beavo JA: Modulation of Leydig cell function by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 8A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:19925-19930. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0609483103 |

||||

| 33 Johnstone TB, Smith KH, Koziol-White CJ, Li F, Kazarian AG, Corpuz ML, Shumyatcher M, Ehlert FJ, Himes BE, Panettieri RA, Jr., Ostrom RS: PDE8 Is Expressed in Human Airway Smooth Muscle and Selectively Regulates cAMP Signaling by beta2-Adrenergic Receptors and Adenylyl Cyclase 6. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018;58:530-541. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2017-0294OC |

||||

| 34 Bebok Z, Collawn JF, Wakefield J, Parker W, Li Y, Varga K, Sorscher EJ, Clancy JP: Failure of cAMP agonists to activate rescued deltaF508 CFTR in CFBE41o- airway epithelial monolayers. J Physiol 2005;569:601-615. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096669 |

||||

| 35 Fulcher ML, Gabriel S, Burns KA, Yankaskas JR, Randell SH: Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol Med 2005;107:183-206. | ||||

| 36 Klarenbeek J, Goedhart J, van Batenburg A, Groenewald D, Jalink K: Fourth-generation epac-based FRET sensors for cAMP feature exceptional brightness, photostability and dynamic range: characterization of dedicated sensors for FLIM, for ratiometry and with high affinity. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122513. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122513 |

||||

| 37 Goedhart J, von Stetten D, Noirclerc-Savoye M, Lelimousin M, Joosen L, Hink MA, van Weeren L, Gadella TW, Jr., Royant A: Structure-guided evolution of cyan fluorescent proteins towards a quantum yield of 93%. Nat Commun 2012;3:751. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1738 |

||||

| 38 Chen L, Ye HL, Zhang G, Yao WM, Chen XZ, Zhang FC, Liang G: Autophagy inhibition contributes to the synergistic interaction between EGCG and doxorubicin to kill the hepatoma Hep3B cells. PLoS One 2014;9:e85771. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085771 |

||||

| 39 Fuhrmann M, Jahn HU, Seybold J, Neurohr C, Barnes PJ, Hippenstiel S, Kraemer HJ, Suttorp N: Identification and function of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isoenzymes in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999;20:292-302. https://doi.org/10.1165/ajrcmb.20.2.3140 |

||||

| 40 Smith SJ, Brookes-Fazakerley S, Donnelly LE, Barnes PJ, Barnette MS, Giembycz MA: Ubiquitous expression of phosphodiesterase 7A in human proinflammatory and immune cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003;284:L279-289. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00170.2002 |

||||

| 41 Wright LC, Seybold J, Robichaud A, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ: Phosphodiesterase expression in human epithelial cells. Am J Physiol 1998;275:L694-700. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.4.L694 |

||||

| 42 Cowley EA, Linsdell P: Characterization of basolateral K+ channels underlying anion secretion in the human airway cell line Calu-3. J Physiol 2002;538:747-757. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013300 |

||||

| 43 Preston P, Wartosch L, Gunzel D, Fromm M, Kongsuphol P, Ousingsawat J, Kunzelmann K, Barhanin J, Warth R, Jentsch TJ: Disruption of the K+ channel beta-subunit KCNE3 reveals an important role in intestinal and tracheal Cl- transport. J Biol Chem 2010;285:7165-7175. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.047829 |

||||

| 44 Li C, Krishnamurthy PC, Penmatsa H, Marrs KL, Wang XQ, Zaccolo M, Jalink K, Li M, Nelson DJ, Schuetz JD, Naren AP: Spatiotemporal coupling of cAMP transporter to CFTR chloride channel function in the gut epithelia. Cell 2007;131:940-951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.037 |

||||

| 45 Cheung L, Flemming CL, Watt F, Masada N, Yu DM, Huynh T, Conseil G, Tivnan A, Polinsky A, Gudkov AV, Munoz MA, Vishvanath A, Cooper DM, Henderson MJ, Cole SP, Fletcher JI, Haber M, Norris MD: High-throughput screening identifies Ceefourin 1 and Ceefourin 2 as highly selective inhibitors of multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4). Biochem Pharmacol 2014;91:97-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2014.05.023 |

||||

| 46 Keating D, Marigowda G, Burr L, Daines C, Mall MA, McKone EF, Ramsey BW, Rowe SM, Sass LA, Tullis E, McKee CM, Moskowitz SM, Robertson S, Savage J, Simard C, Van Goor F, Waltz D, Xuan F, Young T, Taylor-Cousar JL, et al.: VX-445-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two Phe508del Alleles. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1612-1620. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1807120 |

||||

| 47 Middleton PG, Mall MA, Drevinek P, Lands LC, McKone EF, Polineni D, Ramsey BW, Taylor-Cousar JL, Tullis E, Vermeulen F, Marigowda G, McKee CM, Moskowitz SM, Nair N, Savage J, Simard C, Tian S, Waltz D, Xuan F, Rowe SM, et al.: Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1809-1819. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1908639 |

||||

| 48 Matthes E, Goepp J, Martini C, Shan J, Liao J, Thomas DY, Hanrahan JW: Variable Responses to CFTR Correctors in vitro: Estimating the Design Effect in Precision Medicine. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:1490. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01490 |

||||

| 49 Soderling SH, Bayuga SJ, Beavo JA: Cloning and characterization of a cAMP-specific cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:8991-8996. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.15.8991 |

||||

| 50 Brown KM, Day JP, Huston E, Zimmermann B, Hampel K, Christian F, Romano D, Terhzaz S, Lee LC, Willis MJ, Morton DB, Beavo JA, Shimizu-Albergine M, Davies SA, Kolch W, Houslay MD, Baillie GS: Phosphodiesterase-8A binds to and regulates Raf-1 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E1533-1542. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1303004110 |

||||

| 51 Koschinski A, Zaccolo M: Activation of PKA in cell requires higher concentration of cAMP than in vitro: implications for compartmentalization of cAMP signalling. Sci Rep 2017;7:14090. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13021-y |

||||

| 52 Huang P, Lazarowski ER, Tarran R, Milgram SL, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ: Compartmentalized autocrine signaling to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator at the apical membrane of airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:14120-14125. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.241318498 |

||||

| 53 Leier G, Bangel-Ruland N, Sobczak K, Knieper Y, Weber WM: Sildenafil acts as potentiator and corrector of CFTR but might be not suitable for the treatment of CF lung disease. Cell Physiol Biochem 2012;29:775-790. https://doi.org/10.1159/000265129 |

||||

| 54 MacKenzie SJ, Baillie GS, McPhee I, MacKenzie C, Seamons R, McSorley T, Millen J, Beard MB, van Heeke G, Houslay MD: Long PDE4 cAMP specific phosphodiesterases are activated by protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of a single serine residue in Upstream Conserved Region 1 (UCR1). Br J Pharmacol 2002;136:421-433. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0704743 |

||||

| 55 Demirbas D, Wyman AR, Shimizu-Albergine M, Cakici O, Beavo JA, Hoffman CS: A yeast-based chemical screen identifies a PDE inhibitor that elevates steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells via PDE8 and PDE4 inhibition. PLoS One 2013;8:e71279. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071279 |

||||

| 56 Golkowski M, Shimizu-Albergine M, Suh HW, Beavo JA, Ong SE: Studying mechanisms of cAMP and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase signaling in Leydig cell function with phosphoproteomics. Cell Signal 2016;28:764-778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.11.014 |

||||

| 57 Monterisi S, Casavola V, Zaccolo M: Local modulation of cystic fibrosis conductance regulator: cytoskeleton and compartmentalized cAMP signalling. Br J Pharmacol 2013;169:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.12017 |

||||

| 58 Montoro DT, Haber AL, Biton M, Vinarsky V, Lin B, Birket SE, Yuan F, Chen S, Leung HM, Villoria J, Rogel N, Burgin G, Tsankov AM, Waghray A, Slyper M, Waldman J, Nguyen L, Dionne D, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Tata PR, et al.: A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes. Nature 2018;560:319-324. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0393-7 |

||||

| 59 Okuda K, Dang H, Kobayashi Y, Carraro G, Nakano S, Chen G, Kato T, Asakura T, Gilmore RC, Morton LC, Lee RE, Mascenik T, Yin WN, Barbosa Cardenas SM, O'Neal YK, Minnick CE, Chua M, Quinney NL, Gentzsch M, Anderson CW, et al.: Secretory Cells Dominate Airway CFTR Expression and Function in Human Airway Superficial Epithelia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:1275-1289. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202008-3198OC |

||||

| 60 Plasschaert LW, Zilionis R, Choo-Wing R, Savova V, Knehr J, Roma G, Klein AM, Jaffe AB: A single-cell atlas of the airway epithelium reveals the CFTR-rich pulmonary ionocyte. Nature 2018;560:377-381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0394-6 |

||||

| 61 van Aubel RA, Smeets PH, Peters JG, Bindels RJ, Russel FG: The MRP4/ABCC4 gene encodes a novel apical organic anion transporter in human kidney proximal tubules: putative efflux pump for urinary cAMP and cGMP. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002;13:595-603. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.V133595 |

||||

| 62 Naren AP, Cobb B, Li C, Roy K, Nelson D, Heda GD, Liao J, Kirk KL, Sorscher EJ, Hanrahan J, Clancy JP: A macromolecular complex of beta 2 adrenergic receptor, CFTR, and ezrin/radixin/moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50 is regulated by PKA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:342-346. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0135434100 |

||||

| 63 Chen ZS, Lee K, Kruh GD: Transport of cyclic nucleotides and estradiol 17-beta-D-glucuronide by multidrug resistance protein 4. Resistance to 6-mercaptopurine and 6-thioguanine. J Biol Chem 2001;276:33747-33754. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M104833200 |

||||

| 64 Copsel S, Garcia C, Diez F, Vermeulem M, Baldi A, Bianciotti LG, Russel FG, Shayo C, Davio C: Multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) regulates cAMP cellular levels and controls human leukemia cell proliferation and differentiation. J Biol Chem 2011;286:6979-6988. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.166868 |

||||

| 65 Lee RJ, Foskett JK: cAMP-activated Ca2+ signaling is required for CFTR-mediated serous cell fluid secretion in porcine and human airways. J Clin Invest 2010;120:3137-3148. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI42992 |

||||

| 66 Klein H, Abu-Arish A, Trinh NT, Luo Y, Wiseman PW, Hanrahan JW, Brochiero E, Sauve R: Investigating CFTR and KCa3.1 Protein/Protein Interactions. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153665. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153665 |

||||

| 67 Vigone G, Shuhaibar LC, Egbert JR, Uliasz TF, Movsesian MA, Jaffe LA: Multiple cAMP Phosphodiesterases Act Together to Prevent Premature Oocyte Meiosis and Ovulation. Endocrinology 2018;159:2142-2152. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2018-00017 |

||||

| 68 Turner MJ, Dauletbaev N, Lands LC, Hanrahan JW: The Phosphodiesterase Inhibitor Ensifentrine Reduces Production of Proinflammatory Mediators in Well Differentiated Bronchial Epithelial Cells by Inhibiting PDE4. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2020;375:414-429. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.120.000080 |

||||

| 69 Cantin AM, Hanrahan JW, Bilodeau G, Ellis L, Dupuis A, Liao J, Zielenski J, Durie P: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function is suppressed in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1139-1144. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200508-1330OC |

||||

| 70 Raju SV, Rasmussen L, Sloane PA, Tang LP, Libby EF, Rowe SM: Roflumilast reverses CFTR-mediated ion transport dysfunction in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Respir Res 2017;18:173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0656-0 |

||||