Corresponding Author: Julian A. Schreiber

Institute for Genetics of Heart Diseases (IfGH), Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University Hospital Münster, Robert-Koch-Straße 45, D-48149 Münster (Germany)

Tel. +49-251-835872, E-Mail j.schreiber@uni-muenster.de

The Special One: Architecture, Physiology and Pharmacology of the TRESK Channel

Julian A. Schreibera,b Martina Düferb Guiscard Seebohma

aUniversity Hospital Münster, Institute for Genetics of Heart Diseases (IfGH), Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Münster, Germany, bUniversity of Münster, Institute of Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry, Department of Pharmacology, Münster, Germany

Introduction – The K2P Channel Family

Potassium (K+) ion channels are essential for the viability and electrical integrity of nearly all living cells [1]. As a result of selective K+ permeation along the concentration gradient they are crucial for the maintenance of membrane potential as well as repolarization [2, 3]. With more than 80 different genes encoding channel-forming subunits (α subunits) K+channels represent the most diverse group of selective ion channels [4]. So far, four different families are known: voltage-gated (Kv), inward rectifying (Kir), Ca2+- or Na+-activated (KCa / KNa), and two pore domain K+ channels (K2P) [5].

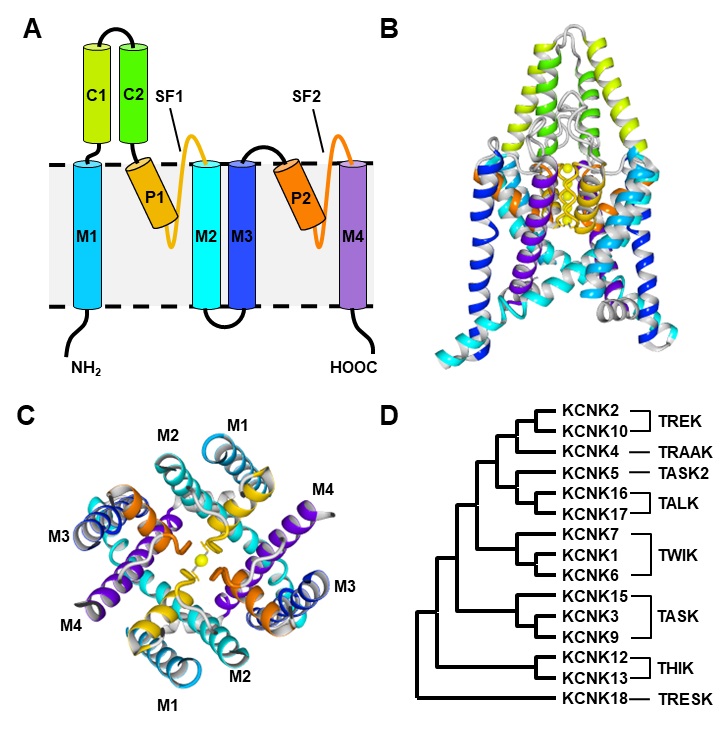

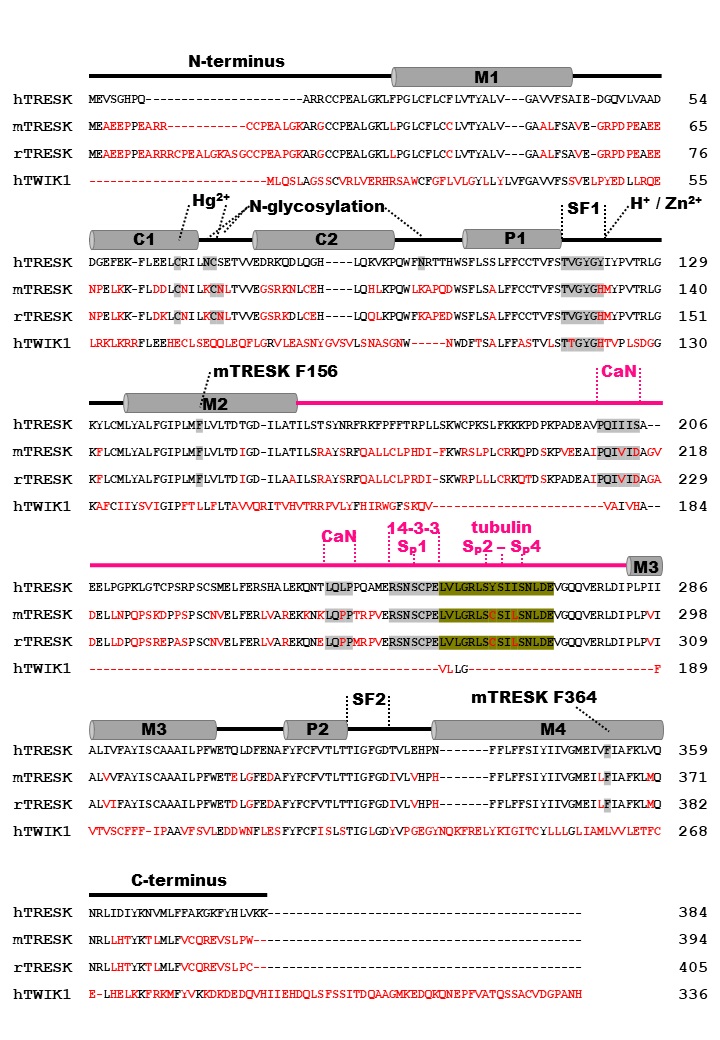

The first member of the mammalian K2P channel family was identified in 1996 [6]. Surprisingly, it shows a novel channel architecture completely different to the other known mammalian K+ channels (Fig. 1A-1C) [6]. While Kv-, Kir and KCa / KNa assemble as tetramers of α subunits, this channel has a homodimeric structure [6]. On the other hand, each monomer possesses two instead of one pore forming region, each comprised of the pore helix (P1/P2) and the pore loop (SF1/SF2) (Fig. 1A, 1C) [6]. Consequently, assembling of two monomers results in the formation of a tetramer-like selectivity filter (SF), that is similar to the SF of other K+ channels ensuring the selective permeation of K+ ions [7]. Heterologous expression of the channel results in an almost linear current-voltage relationship with a weak inward rectification [6]. Therefore, it was named TWIK1, which stands for “tandem of pore domains in a weak inward rectifying K+ channel 1” [6].

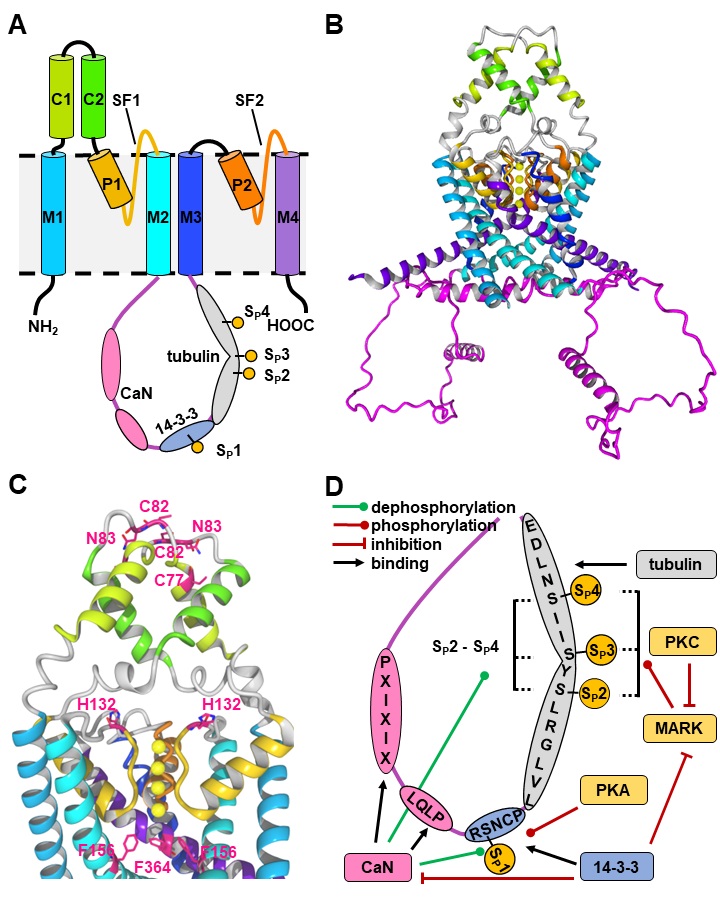

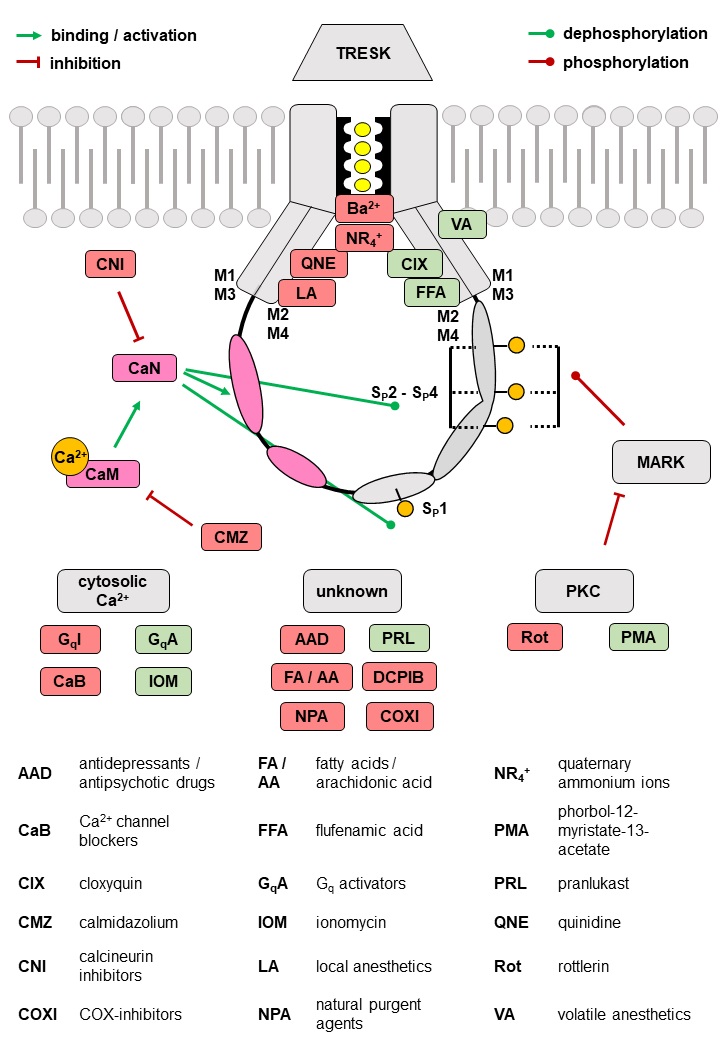

Today, 15 different genes encoding K2P subunits are known, that commonly form homodimers [8]. Recent studies suggest, that heterodimerization can occur for some K2P subunits, which is comprehensible due to their highly related monomer structure [9–12]. Beside the typical pair of pore-forming regions (P1/P2, SF1/SF2) each monomer possesses four transmembrane helices (M1-M4) and two extracellular helices (C1, C2) (Fig. 1A-1C) [13]. In the dimeric channel, C1 and C2 form the typical Cap-structure, that is responsible for the insensitivity of K2P channels to most classical K+ channel pore blockers and peptide toxins [13, 14]. Interestingly, many K2P channels have an extended intracellular C-terminus, that is involved in functional modulation of the ion channel by phospholipids, fatty acids, and regulatory proteins [15, 16].

Since K2P channels adopt conductive states over a broad range of voltages, they are also called K+ leak channels [17]. However, their open probability can be effectively modulated by different entities like membrane tension, H+, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), volatile anesthetics or temperature [18]. Contrary to Kv channels, most K2P channels do not possess an intracellular gate [18]. Therefore, the gating process is mainly controlled by the SF, that shows a behavior similar to C-type inactivation of Kv channels [19–22]. However, recent studies identified the X gate at TASK channels, that is located at the inner vestibule controlling the pharmacodynamics of TASK-1 channel inhibitors [23].

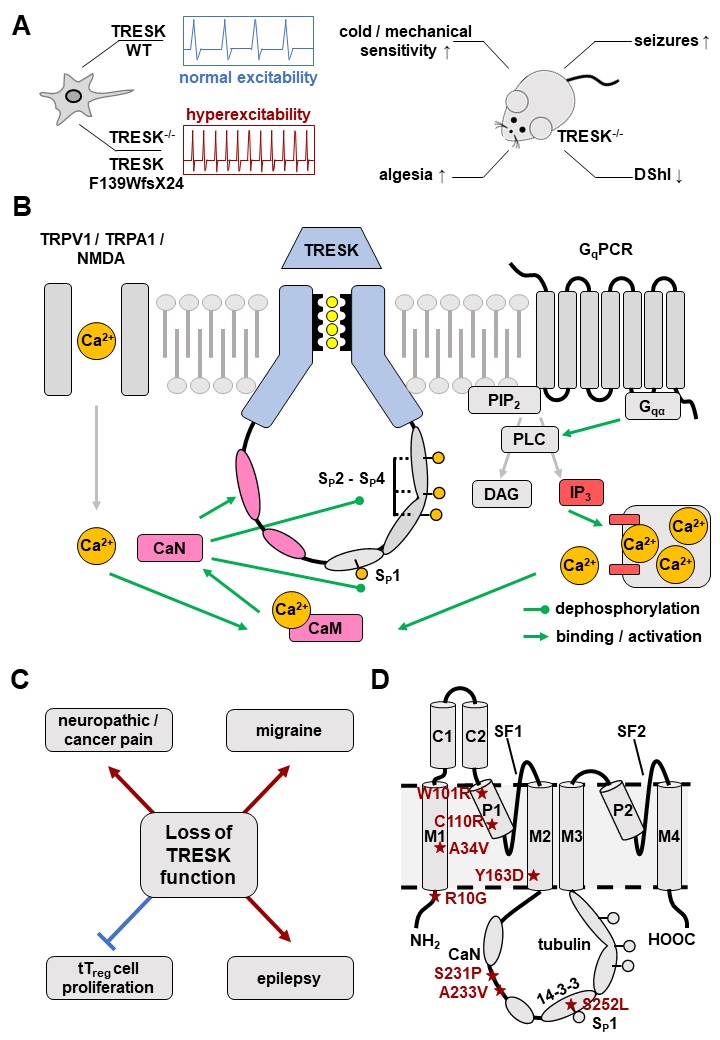

Based on their functional properties K2P channels can be subdivided into subfamilies of weakly inward rectifying (TWIK), TWIK-related (TREK), acid-sensitive (TASK), arachidonic acid-sensitive (TRAAK), alkaline-activated (TALK), halothane-inhibited (THIK) and TWIK-related spinal cord (TRESK) K+ channels (Fig. 1D) [24]. The last identified K2P channel is TRESK, which was found in 2003 by analysis of the human genome data base [25]. Although structural similarity is assumed, sequence identity compared to the other K2P channels is only 13 - 19 % [25]. Low sequence identity as well as several unique features render TRESK as the most diverse channel of the K2P family. The structural, biophysical, and pharmacological properties of TRESK are explained in the following paragraphs of this review. Furthermore, the significance of TRESK channels for physiological and pathophysiological processes is discussed in detail.

We thank Prof. Dr. Bernhard Wünsch for carefully proofreading the manuscript.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written by JAS with the help of MD and GS.

The authors declare that no conflict of interests exists.

| 1 Kuang Q, Purhonen P, Hebert H: Structure of potassium channels. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015;72:3677-3693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-1948-5 |

||||

| 2 Wiedmann F, Frey N, Schmidt C: Two-Pore-Domain Potassium (K2P-) Channels: Cardiac Expression Patterns and Disease-Specific Remodelling Processes. Cells 2021;10:2914. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10112914 |

||||

| 3 Miller C: An overview of the potassium channel family. Genome Biol 2000;1:Reviews0004.1-0004.5. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2000-1-4-reviews0004 |

||||

| 4 Trimmer JS: Subcellular localization of K+ channels in mammalian brain neurons: Remarkable precision in the midst of extraordinary complexity. Neuron 2015;85:238-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.042 |

||||

| 5 Taura J, Kircher DM, Gameiro-Ros I, Slesinger PA: Comparison of K+ Channel Families; in Gamper N, Wang K (eds): Pharmacology of Potassium Channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2021;267:1-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2021_460 |

||||

| 6 Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Duprat F, Lazdunski M, Romey G, Barhanin J: TWIK-1, a ubiquitous human weakly inward rectifying K+ channel with a novel structure. EMBO J 1996;15:1004-1111. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00437.x |

||||

| 7 Turney TS, Li V, Brohawn SG: Structural Basis for pH-gating of the K+ channel TWIK1 at the selectivity filter. Nat Commun 2022;13:3232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30853-z |

||||

| 8 Lotshaw DP: Biophysical, pharmacological, and functional characteristics of cloned and native mammalian two-pore domain K+ channels. Cell Biochem Biophys 2007;47:209-256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-007-0007-8 |

||||

| 9 Blin S, Chatelain FC, Feliciangeli S, Kang D, Lesage F, Bichet D: Tandem pore domain halothane-inhibited K+channel subunits THIK1 and THIK2 assemble and form active channels. J Biol Chem 2014;289:28202-28212. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.600437 |

||||

| 10 Berg AP, Talley EM, Manger JP, Bayliss DA: Motoneurons express heteromeric TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ (TASK) channels containing TASK-1 (KCNK3) and TASK-3 (KCNK9) subunits. J Neurosci 2004;24:6693-6702. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1408-04.2004 |

||||

| 11 Royal P, Andres-Bilbe A, Ávalos Prado P, Verkest C, Wdziekonski B, Schaub S, Baron A, Lesage F, Gasull X, Levitz J, Sandoz G: Migraine-Associated TRESK Mutations Increase Neuronal Excitability through Alternative Translation Initiation and Inhibition of TREK. Neuron 2019;101:232-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.11.039 |

||||

| 12 Pope L, Arrigoni C, Lou H, Bryant C, Gallardo-Godoy A, Renslo AR, Minor DL.: Protein and Chemical Determinants of BL-1249 Action and Selectivity for K 2P Channels. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2018;9:3153-3165. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00337 |

||||

| 13 Brohawn SG, del Mármol J, MacKinnon R: Crystal Structure of the Human K2P TRAAK, a Lipid- and Mechano-Sensitive K+ Ion Channel. Science 2012;335:436-441. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1213808 |

||||

| 14 Miller AN, Long SB: Crystal Structure of the Human Two-Pore Domain Potassium Channel K2P1. Science 2012;335:432-436. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1213274 |

||||

| 15 Riel EB, Jürs BC, Cordeiro S, Musinszki M, Schewe M, Baukrowitz T: The versatile regulation of K2P channels by polyanionic lipids of the phosphoinositide and fatty acid metabolism. J Gen Phys 2022;154:e202112989. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.202112989 |

||||

| 16 Niemeyer MI, Cid LP, Paulais M, Teulon J, Sepúlveda F: Phosphatidylinositol (4, 5)-bisphosphate dynamically regulates the K2P background K+ channel TASK-2. Sci Rep 2017;7:45407. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45407 |

||||

| 17 Enyedi P, Czirják G: Molecular background of leak K+ currents: Two-pore domain potassium channels. Physiol Rev 2010;90:559-605. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00029.2009 |

||||

| 18 Natale AM, Deal PE, Minor DL: Structural Insights into the Mechanisms and Pharmacology of K2P Potassium Channels. J Mol Biol 2021;433:166995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166995 |

||||

| 19 Zhang Q, Fu J, Zhang S, Guo P, Liu S, Shen J, Guo J, Yang H: 'C-type' closed state and gating mechanisms of K2P channels revealed by conformational changes of the TREK-1 channel. J Mol Cell Biol 2022;02120:1-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjac002 |

||||

| 20 Proks P, Schewe M, Conrad LJ, Rao S, Rathje K, Rödström KEJ, Carpenter EP, Baukrowitz T, Tucker SJ: Norfluoxetine inhibits TREK-2 K2P channels by multiple mechanisms including state-independent effects on the selectivity filter gate. J Gen Phys 2021;153:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.202012812 |

||||

| 21 Lolicato M, Natale AM, Abderemane-Ali F, Crottès D, Capponi S, Duman R, Wagner A, Rosenberg JM, Grabe M, Minor DL: K2Pchannel C-type gating involves asymmetric selectivity filter order-disorder transitions. Sci Adv 2020;6:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc9174 |

||||

| 22 Kopec W, Rothberg BS, de Groot BL: Molecular mechanism of a potassium channel gating through activation gate-selectivity filter coupling. Nat Commun 2019;10:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13227-w |

||||

| 23 Rödström KEJ, Kiper AK, Zhang W, Rinné S, Pike ACW, Goldstein M, Conrad LJ, Delbeck M, Hahn MG, Meier H, Platzk M, Quigley A, Speedman D, Shrestha L, Mukhopadhyay SMM, Burgess-Brown NA, Tucker SJ, Müller T, Decher N, Carpenter EP: A lower X-gate in TASK channels traps inhibitors within the vestibule. Nature 2020;582:443-447. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2250-8 |

||||

| 24 Kamuene JM, Xu Y, Plant LD: The Pharmacology of Two-Pore Domain Potassium Channels; in Gamper N, Wang K (eds): Pharmacology of Potassium Channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2021;267:417-443. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2021_462 |

||||

| 25 Sano Y, Inamura K, Miyake A, Mochizuki S, Kitada C, Yokoi H, Nozawa K, Okada H, Matsushime H, Furuichi K: A novel two-pore domain K+ channel, TRESK, is localized in the spinal cord. J Biol Chem 2003;278:27406-27412. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M206810200 |

||||

| 26 Czirják G, Enyedi P: Targeting of calcineurin to an NFAT-like docking site is required for the calcium-dependent activation of the background K+ channel, TRESK. J Biol Chem 2006;281:14677-14682. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M602495200 |

||||

| 27 Kang D, Mariash E, Kim D: Functional expression of TRESK-2, a new member of the tandem-pore K + channel family. J Biol Chem 2004;279:28063-28070. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M402940200 |

||||

| 28 Rahm AK, Wiedmann F, Gierten J, Schmidt C, Schweizer PA, Becker R, Katus HA, Thomas D: Functional characterization of zebrafish K2P18.1 (TRESK) two-pore-domain K+ channels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2014;387:291-300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-013-0945-1 |

||||

| 29 Callejo G, Giblin JP, Gasull X: Modulation of TRESK Background K+ Channel by Membrane Stretch. PLoS One 2013;8:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064471 |

||||

| 30 Czirják G, Tóth ZE, Enyedi P: The Two-pore Domain K+ Channel, TRESK, Is Activated by the Cytoplasmic Calcium Signal through Calcineurin. J Biol Chem 2004;279:18550-18558. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M312229200 |

||||

| 31 Lengyel M, Czirják G, Enyedi P: TRESK background potassium channel is not gated at the helix bundle crossing near the cytoplasmic end of the pore. PLoS One 2018;13:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197622 |

||||

| 32 Lengyel M, Dobolyi A, Czirják G, Enyedi P: Selective and state-dependent activation of TRESK (K2P 18.1) background potassium channel by cloxyquin. Br J Pharmacol 2017;174:2102-2113. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13821 |

||||

| 33 Dobler T, Springauf A, Tovornik S, Weber M, Schmitt A, Sedlmeier R, Wischmeyer E, Döring F: TRESK two-pore-domain K+ channels constitute a significant component of background potassium currents in murine dorsal root ganglion neurones. J Physiol 2007;585:867-879. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145649 |

||||

| 34 Rajan S, Wischmeyer E, Liu GX, Preisig-Müller R, Daut J, Karschin A, Derst C.: TASK-3, a novel tandem pore domain acid-sensitive K+ channel. An extracellular histidine as pH sensor. J Biol Chem 2000;275:16650-16657. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M000030200 |

||||

| 35 Keshavaprasad B, Liu C, Au JD, Kindler CH, Cotten JF, Yost CS: Species-specific differences in response to anesthetics and other modulators by the K2P channel TRESK. Anesth Analg 2005;101:1042-1049. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000168447.87557.5a |

||||

| 36 Czirják G, Enyedi P: Zinc and mercuric ions distinguish TRESK from the other two-pore-domain K+ channels. Mol Pharmacol 2006;69:1024-1032. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.105.018556 |

||||

| 37 Egenberger B, Polleichtner G, Wischmeyer E, Döring F: N-linked glycosylation determines cell surface expression of two-pore-domain K+ channel TRESK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;391:1262-1267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.056 |

||||

| 38 Giblin JP, Etayo I, Castellanos A, Andres-Bilbe A, Gasull X: Anionic Phospholipids Bind to and Modulate the Activity of Human TRESK Background K + Channel. Mol Neurobiol 2019;56:2524-2541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1244-0 |

||||

| 39 Czirják G, Enyedi P: The LQLP calcineurin docking site is a major determinant of the calcium-dependent activation of human TRESK background K+ channel. J Biol Chem 2014;289:29506-29518. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.577684 |

||||

| 40 Czirják G, Enyedi P: TRESK background K+ channel is inhibited by phosphorylation via two distinct pathways. J Biol Chem 2010;285:14549-14557. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.102020 |

||||

| 41 Czirják G, Vuity D, Enyedi P: Phosphorylation-dependent binding of 14-3-3 proteins controls TRESK regulation. J Biol Chem 2008;283:15672-15680. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M800712200 |

||||

| 42 Chaudhri M, Scarabel M, Aitken A: Mammalian and yeast 14-3-3 isoforms form distinct patterns of dimers in vivo . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003;300:679-685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02902-9 |

||||

| 43 Enyedi P, Veres I, Braun G, Czirják G: Tubulin binds to the cytoplasmic loop of TRESK background K+ channel in vitro . PLoS One 2014;9:e97854. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097854 |

||||

| 44 Matenia D, Mandelkow E-M: The tau of MARK: a polarized view of the cytoskeleton. Trends Biochem Sci 2009;34:332-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2009.03.008 |

||||

| 45 Braun G, Nemcsics B, Enyedi P, Czirják G: Tresk background K+ channel is inhibited by PAR-1/MARK microtubule affinity-regulating kinases in Xenopus oocytes. PLoS One 2011;6:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028119 |

||||

| 46 Rahm AK, Gierten J, Kisselbach J, Staudacher I, Staudacher K, Schweizer PA, Becker R, Katus HA, Thomas D: PKC-dependent activation of human K 2P18.1 K + channels. Br J Pharmacol 2012;166:764-773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01813.x |

||||

| 47 Pergel E, Lengyel M, Enyedi P, Czirják G: TRESK (K2P18.1) background potassium channel is activated by novel-type protein kinase C via dephosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol 2019;95:661-672. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.119.116269 |

||||

| 48 Lafrenière RG, Cader MZ, Poulin JF, Andres-Enguix I, Simoneau M, Gupta N, Boisvert K, Lafrenière F, McLaughlan S, Dube MP, Marcinkiewicz MM, Ramagopalan S, Ansorge O, Brais B, Sequeiros J, Pereira-Monteiro JM, Griffiths LR, Tucker SJ, Ebers G, Rouleau GA: A dominant-negative mutation in the TRESK potassium channel is linked to familial migraine with aura. Nat Med 2010;16:1157-1160. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2216 |

||||

| 49 Kang D, Kim D: TREK-2 (K2P10.1) and TRESK (K2P18.1) are major background K+ channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006;291:138-146. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00629.2005 |

||||

| 50 Yoo SH, Liu J, Sabbadini M, Au P, Xie G xi, Yost CS: Regional expression of the anesthetic-activated potassium channel TRESK in the rat nervous system. Neurosci Lett 2009;465:79-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2009.08.062 |

||||

| 51 Tulleuda A, Cokic B, Callejo G, Saiani B, Serra J, Gasull X: TRESK channel contribution to nociceptive sensory neurons excitability: Modulation by nerve injury. Mol Pain 2011;7:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-7-30 |

||||

| 52 Kollert S, Dombert B, Döring F, Wischmeyer E: Activation of TRESK channels by the inflammatory mediator lysophosphatidic acid balances nociceptive signalling. Sci Rep 2015;5:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12548 |

||||

| 53 Manteniotis S, Lehmann R, Flegel C, Vogel F, Hofreuter A, Schreiner BSP, Altmüller J, Becker C, Schöbel N, Hatt H, Gisselmann G: Comprehensive RNA-Seq Expression Analysis of Sensory Ganglia with a Focus on Ion Channels and GPCRs in Trigeminal Ganglia. PLoS One 2013;8:e79523. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079523 |

||||

| 54 Weir GA, Pettingill P, Wu Y, Duggal G, Ilie AS, Akerman CJ, Cader MZ: The role of TRESK in discrete sensory neuron populations and somatosensory processing. Front Mol Neurosci 2019;12:1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00170 |

||||

| 55 Castellanos A, Pujol-Coma A, Andres-Bilbe A, Negm A, Callejo G, Soto D, Noel J, Comes N, Gasull X: TRESK background K+ channel deletion selectively uncovers enhanced mechanical and cold sensitivity. J Physiol 2020;598:1017-1038. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP279203 |

||||

| 56 Lalic T, Steponenaite A, Wei L, Vasudevan SR, Mathie A, Peirson SN, Lall GS, Cader MZ: TRESK is a key regulator of nocturnal suprachiasmatic nucleus dynamics and light adaptive responses. Nat Commun 2020;11:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17978-9 |

||||

| 57 Guo Z, Qiu CS, Jiang X, Zhang J, Li F, Liu Q, Dhaka A, Cao Y-Q: TRESK K+ channel activity regulates trigeminal nociception and headache. eNeuro 2019;6:ENEURO.0236-19.2019. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0236-19.2019 |

||||

| 58 Huang D, Li S, Dhaka A, Story GM, Cao Y-Q: Expression of the transient receptor potential channels TRPV1, TRPA1 and TRPM8 in mouse trigeminal primary afferent neurons innervating the dura. Mol Pain 2012;66:1-19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-8-66 |

||||

| 59 Koo JY, Jang Y, Cho H, Lee CH, Jang KH, Chang YH, Shin J, Oh U: Hydroxy-α-sanshool activates TRPV1 and TRPA1 in sensory neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience 2007;26:1139-1147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05743.x |

||||

| 60 Breese NM, George AC, Pauers LE, Stucky CL: Peripheral inflammation selectively increases TRPV1 function in IB4-positive sensory neurons from adult mouse. Pain 2005;115:37-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.010 |

||||

| 61 Lengyel M, Hajdu D, Dobolyi A, Rosta J, Czirják G, Dux M, Enyedi P: TRESK background potassium channel modifies the TRPV1-mediated nociceptor excitability in sensory neurons. Cephalalgia 2021;41:827-838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102421989261 |

||||

| 62 Guo Z, Cao YQ: Over-expression of TRESK K+ channels reduces the excitability of trigeminal ganglion nociceptors. PLoS One 2014;9:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087029 |

||||

| 63 Zhou J, Yao SL, Yang CX, Zhong JY, Wang HB, Zhang Y: TRESK gene recombinant adenovirus vector inhibits capsaicin-mediated substance P release from cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Med Rep 2012;5:1049-1052. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2012.778 |

||||

| 64 Louis-Gray K, Tupal S, Premkumar LS: TRPV1: A Common Denominator Mediating Antinociceptive and Antiemetic Effects of Cannabinoids. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:10016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231710016 |

||||

| 65 Nakato R, Manabe N, Hanayama K, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Haruma K: Diagnosis and treatments for oropharyngeal dysphagia: effects of capsaicin evaluated by newly developed ultrasonographic method. J Smooth Muscle Res 2020;56:46-57. https://doi.org/10.1540/jsmr.56.46 |

||||

| 66 Balcziak LK, Russo AF: Dural Immune Cells, CGRP, and Migraine. Front Neurol 2022;13:874193. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.874193 |

||||

| 67 Muñoz M, Coveñas R: Involvement of substance P and the NK-1 receptor in human pathology. Amino Acids 2014;46:1727-1750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-014-1736-9 |

||||

| 68 Ruck T, Bock S, Pfeuffer S, Schroeter CB, Cengiz D, Marciniak P, Lindner M, Herrmann A, Liebmann M, Kovac S, Gola L, Rolfes L, Pawlitzki M, Opel N, Hahn T, Dannlowski U, Pap T, Luessi F, Schreiber JA, Wünsch B, et al.: K2P18.1 translates T cell receptor signals into thymic regulatory T cell development. Cell Res 2022;32:72-88. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-021-00580-z |

||||

| 69 Bruner JK, Zou B, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Schmidt K, Li M: Identification of novel small molecule modulators of K2P18.1 two-pore potassium channel. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;740:603-610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.021 |

||||

| 70 Marsh B, Acosta C, Djouhri L, Lawson SN: Leak K + channel mRNAs in dorsal root ganglia: Relation to inflammation and spontaneous pain behaviour. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2012;49:375-386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2012.01.002 |

||||

| 71 Kim GT, Siregar AS, Kim EJ, Lee ES, Nyiramana MM, Woo MS, Hah Y-S, Han J, Kang D: Upregulation of tresk channels contributes to motor and sensory recovery after spinal cord injury. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21238997 |

||||

| 72 Veale EL, Mathie A: Aristolochic acid, a plant extract used in the treatment of pain and linked to Balkan endemic nephropathy, is a regulator of K2P channels. Br J Pharmacol 2016;173:1639-1652. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13465 |

||||

| 73 Falkenburger BH, Dickson EJ, Hille B: Quantitative properties and receptor reserve of the DAG and PKC branch of Gq-coupled receptor signaling. J Gen Physiol 2013;141:537-555. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.201210887 |

||||

| 74 Han J, Kang D: TRESK channel as a potential target to treat T-cell mediated immune dysfunction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;390:1102-1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.076 |

||||

| 75 Pottosin II, Bonales-Alatorre E, Valencia-Cruz G, Mendoza-Magaña ML, Dobrovinskaya OR: TRESK-like potassium channels in leukemic T cells. Pflugers Arch 2008;456:1037-1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-008-0481-x |

||||

| 76 Sánchez-Miguel DS, García-Dolores F, Rosa Flores-Márquez M, Delgado-Enciso I, Pottosin I, Dobrovinskaya O: TRESK potassium channel in human T lymphoblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013;434:273-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.115 |

||||

| 77 Bobak N, Bittner S, Andronic J, Hartmann S, Mühlpfordt F, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Wolf K, Schmelter C, Göbel K, Meuth P, Zimmermann H, Döring F, Wischmeyer E, Budde T, Wiendl H, Meuth SG, Sukhorukov VL: Volume regulation of murine T lymphocytes relies on voltage-dependent and two-pore domain potassium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2011;1808:2036-2044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.04.013 |

||||

| 78 Brown CC, Gottschalk RA: Volume control: Turning the dial on regulatory T cells. Cell 2021;184:3847-3849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.015 |

||||

| 79 Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK: Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 2006;441:235-238. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04753 |

||||

| 80 Shkodra M, Caraceni A: Treatment of Neuropathic Pain Directly Due to Cancer: An Update. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14081992 |

||||

| 81 Liu JP, Jing HB, Xi K, Zhang ZX, Jin ZR, Cai SQ, Tian Y, Cai J, Xing G-G: Contribution of TRESK two-pore domain potassium channel to bone cancer-induced spontaneous pain and evoked cutaneous pain in rats. Mol Pain 2021;17:1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/17448069211023230 |

||||

| 82 Yang Y, Li S, Jin ZR, Jing HB, Zhao HY, Liu BH, Liang YJ, Cai J, Wan Y, Xing G-G: Decreased abundance of TRESK two-pore domain potassium channels in sensory neurons underlies the pain associated with bone metastasis. Sci Signal 2018;11:eaao5150. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aao5150 |

||||

| 83 Zhou J, Yang CX, Zhong JY, Wang HB: Intrathecal TRESK gene recombinant adenovirus attenuates spared nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Neuroreport 2013;24:131-136. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0b013e32835d8431 |

||||

| 84 Zhou J, Lin W, Chen H, Fan Y, Yang C: TRESK contributes to pain threshold changes by mediating apoptosis via MAPK pathway in the spinal cord. Neuroscience 2016;339:622-633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.10.039 |

||||

| 85 Zhou J, Chen H, Yang C, Zhong J, He W, Xiong Q: Reversal of TRESK Downregulation Alleviates Neuropathic Pain by Inhibiting Activation of Gliocytes in the Spinal Cord. Neurochem Res 2017;42:1288-1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-016-2170-z |

||||

| 86 Liu P, Cheng Y, Xu H, Huang H, Tang S, Song F, Zhou J: TRESK Regulates Gm11874 to Induce Apoptosis of Spinal Cord Neurons via ATP5i Mediated Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage. Neurochem Res 2021;46:1970-1980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-021-03318-w |

||||

| 87 Pettingill P, Weir GA, Wei T, Wu Y, Flower G, Lalic T, Handel A, Duggal G, Chintawar S, Cheung J, Arunasalam K, Couper E, Haupt LM, Griffiths LR, Bassett A, Cowley SA, Cader MZ: A causal role for TRESK loss of function in migraine mechanisms. Brain 2019;142:3852-3867. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz342 |

||||

| 88 Gada K, Plant LD: Two-pore domain potassium channels: emerging targets for novel analgesic drugs: IUPHAR Review 26. Br J Pharmacol 2019;176:256-266. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14518 |

||||

| 89 Rainero I, Rubino E, Gallone S, Zavarise P, Carli D, Boschi S, Fenoglio P, Savi L, Gentile S, Benna P, Pinessi L, Dalla Volta G: KCNK18 (TRESK) genetic variants in Italian patients with migraine. Headache 2014;54:1515-1522. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12439 |

||||

| 90 Andres-Enguix I, Shang L, Stansfeld PJ, Morahan JM, Sansom MSP, Lafrenière RG, Roy B, Griffiths LR, Rouleau GA, Ebers GC, Cader ZM, Tucker SJ: Functional analysis of missense variants in the TRESK (KCNK18) K + channel. Sci Rep 2012;2:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00237 |

||||

| 91 Imbrici P, Nematian-Ardestani E, Hasan S, Pessia M, Tucker SJ, D'Adamo MC: Altered functional properties of a missense variant in the TRESK K+ channel (KCNK18) associated with migraine and intellectual disability. Pflugers Arch 2020;472:923-930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-020-02382-5 |

||||

| 92 Pavinato L, Nematian-Ardestani E, Zonta A, de Rubeis S, Buxbaum J, Mancini C, Bruselles A, Tartaglia M, Pessia M, Tucker SJ, D'Adamo MC, Brusco A: Kcnk18 biallelic variants associated with intellectual disability and neurodevelopmental disorders alter tresk channel activity. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:6064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22116064 |

||||

| 93 Han JY, Jang JH, Park J, Lee IG: Targeted next-generation sequencing of Korean patients with developmental delay and/or intellectual disability. Front Pediatr 2018;6:1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00391 |

||||

| 94 Guo Z, Liu P, Ren F, Cao YQ: Nonmigraine-associated TRESK K+ channel variant c110r does not increase the excitability of trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol 2014;112:568-579. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00267.2014 |

||||

| 95 Markel KA, Curtis D: Study of variants in genes implicated in rare familial migraine syndromes and their association with migraine in 200,000 exome‐sequenced UK Biobank participants. Ann Hum Genet 2022;86:353-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahg.12484 |

||||

| 96 Huang W, Ke Y, Zhu J, Liu S, Cong J, Ye H, Guo Y, Wang K, Zhang Z, Meng W, Gao T-M, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W, Chen R: TRESK channel contributes to depolarization-induced shunting inhibition and modulates epileptic seizures. Cell Rep 2021;36:109404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109404 |

||||

| 97 Huntemann N, Bittner S, Bock S, Meuth SG, Ruck T: Mini-Review: Two Brothers in Crime - The Interplay of TRESK and TREK in Human Diseases. Neurosci Lett 2022;769:136376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136376 |

||||

| 98 Liu C, Au JD, Zou HL, Cotten JF, Yost CS: Potent activation of the human tandem pore domain K channel TRESK with clinical concentrations of volatile anesthetics. Anesth Analg 2004;99:1715-1722. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000136849.07384.44 |

||||

| 99 Zhou W, Guan Z: Ion Channels in Anesthesia. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021;1349:401-413. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4254-8_19 |

||||

| 100 Luethy A, Boghosian JD, Srikantha R, Cotten JF: Halogenated ether, alcohol, and alkane anesthetics activate TASK-3 tandem pore potassium channels likely through a common mechanism. Mol Pharmacol 2017;91:620-629. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.117.108290 |

||||

| 101 Monteillier A, Loucif A, Omoto K, Stevens EB, Vicente SL, Saintot PP, Cao L, Pryde DC: Investigation of the structure activity relationship of flufenamic acid derivatives at the human TRESK channel K2P18.1. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2016;26:4919-4924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.09.020 |

||||

| 102 Brosnan R, Gong D, Cotten J, Keshavaprasad B, Yost CS, Eger EI, Sonner JM.: Chirality in anesthesia II: Stereoselective modulation of ion channel function by secondary alcohol enantiomers. Anesth Analg 2006;103:86-91. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000221437.87338.af |

||||

| 103 Wright PD, Weir G, Cartland J, Tickle D, Kettleborough C, Cader MZ, Jerman J: Cloxyquin (5-chloroquinolin-8-ol) is an activator of the two-pore domain potassium channel TRESK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013;441:463-468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.10.090 |

||||

| 104 Lengyel M, Erdélyi F, Pergel E, Bálint-Polonka Á, Dobolyi A, Bozsaki P, Dux M, Kiraly K, Hegedus T, Czirjak G, Matyus P, Enyedi P: Chemically modified derivatives of the activator compound cloxyquin exert inhibitory effect on TRESK (K2P18.1) background potassium channel. Mol Pharmacol 2019;95:652-660. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.118.115626 |

||||

| 105 Takahira M, Mayumi AE, Norimasa S, Ae S, Sugiyama K: Fenamates and diltiazem modulate lipid-sensitive mechano-gated 2P domain K + channels. Eur J Physiol 2005;451:474-478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-005-1492-5 |

||||

| 106 Wright PD, McCoull D, Walsh Y, Large JM, Hadrys BW, Gaurilcikaite E, Byrom L, Veale EL, Jerman J, Mathie A: Pranlukast is a novel small molecule activator of the two-pore domain potassium channel TREK2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019;520:35-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.09.093 |

||||

| 107 Schewe M, Sun H, Mert Ü, Mackenzie A, Pike ACW, Schulz F, Constantin C, Vowinkel KS, Conrad LJ, Kiper AK, Gonzalez W, Musinszki M, Tegtmeier M, Pryde DC, Belabed H, Nazare M, de Groot BL, Decher N, Fakler B, Carpenter EP, et al.: A pharmacological master key mechanism that unlocks the selectivity filter gate in K channels. Science 2019;363:875-880. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav0569 |

||||

| 108 Subramanian H, Döring F, Kollert S, Rukoyatkina N, Sturm J, Gambaryan S, Stellzig-Eisenhauer A, Meyer-Marcotty P, Eigenthaler M, Wischmeyer E: PTH1R mutants found in patients with primary failure of tooth eruption disrupt G-protein signaling. PLoS One 2016;11:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167033 |

||||

| 109 Piechotta PL, Rapedius M, Stansfeld PJ, Bollepalli MK, Erhlich G, Andres-Enguix I, Fritzenschaft H, Decher N, Sansom MSP, Tucker SJ, Baukrowitz, T: The pore structure and gating mechanism of K2P channels. EMBO J 2011;30:3607-3619. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2011.268 |

||||

| 110 Kim S, Lee Y, Tak HM, Park HJ, Sohn YS, Hwang S, Han J, Kang D, Lee KW: Identification of blocker binding site in mouse TRESK by molecular modeling and mutational studies. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2013;1828:1131-1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.11.021 |

||||

| 111 Park H, Kim EJ, Han J, Han J, Kang D: Effects of analgesics and antidepressants on TREK-2 and TRESK currents. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 2016;20:379-385. https://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.4.379 |

||||

| 112 Kang D, Kim GT, Kim EJ, La JH, Lee JS, Lee ES, Park JY, Hong SG, Han J: Lamotrigine inhibits TRESK regulated by G-protein coupled receptor agonists. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;367:609-615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.008 |

||||

| 113 Walsh Y, Leach M, Veale EL, Mathie A: Block of TREK and TRESK K2P channels by lamotrigine and two derivatives sipatrigine and CEN-092. Biochem Biophys Rep 2021;26:101021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.101021 |

||||

| 114 Dong YY, Pike ACW, Mackenzie A, McClenaghan C, Aryal P, Dong L, Quigley A, Grieben M, Goubin S, Mukhopadhyay S, Ruda GF, Clausen MV, Cao L, Brennan PE, Burgess-Brown NA, Sansom MSP, Tucker SJ, Carpenter EP: K2P channel gating mechanisms revealed by structures of TREK-2 and a complex with Prozac. Science 2015;347:1256-1259. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261512 |

||||

| 115 Lv J, Liang Y, Zhang S, Lan Q, Xu Z, Wu X, Kang L, Ren J, Cao Y, Wu T, Lin KL, Yung KKL, Cao X, Pang J, Zhou P: DCPIB, an Inhibitor of Volume-Regulated Anion Channels, Distinctly Modulates K2P Channels. ACS Chem Neurosci 2019;10:2786-2793. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00010 |

||||

| 116 Park H, Kim EJ, Ryu JH, Lee DK, Hong SG, Han J, Han J, Kang D: Verapamil inhibits TRESK (K2p18.1) current in trigeminal ganglion neurons independently of the blockade of Ca2+ influx. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19071961 |

||||

| 117 Huang Y, Chen SR, Pan HL: Calcineurin Regulates Synaptic Plasticity and Nociceptive Transmissionat the Spinal Cord Level. Neuroscientist 2022;28:628-638. https://doi.org/10.1177/10738584211046888 |

||||

| 118 Ferrari U, Empl M, Kim KS, Sostak P, Förderreuther S, Straube A: Calcineurin inhibitor-induced headache: Clinical characteristics and possible mechanisms. Headache 2005;45:211-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05046.x |

||||

| 119 Beltrán LR, Dawid C, Beltrán M, Gisselmann G, Degenhardt K, Mathie K, Hofmann T, Hatt H: The pungent substances piperine, capsaicin, 6-gingerol and polygodial inhibit the human two-pore domain potassium channels TASK-1, TASK-3 and TRESK. Front Pharmacol 2013;4:1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00141 |

||||

| 120 Beltrán LR, Dawid C, Beltrán M, Levermann J, Titt S, Thomas S, Pürschel V, Satalik M, Gisselmann G, Hofmann T, Hatt H: The effect of pungent and tingling compounds from Piper nigrum L. on background K+ currents. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00408 |

||||

| 121 Bautista DM, Sigal YM, Milstein AD, Garrison JL, Zorn JA, Tsuruda PR, Nicoll RA, Julius D: Pungent agents from Szechuan peppers excite sensory neurons by inhibiting two-pore potassium channels. Nat Neurosci 2008;11:772-779. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2143 |

||||

| 122 Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K: MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018;35:1547-1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096 |

||||

| 123 Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A, Potapenko A, Bridgland A, Meyer C, Kohl SAA, Ballard AJ, Cowie A, Romera-Paredes B, Nikolov S, Jain R, Adler J, Back T, et al.: Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021;596:583-589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 |

||||

| 124 Varadi M, Anyango S, Deshpande M, Nair S, Natassia C, Yordanova G, Yuan D, Stroe O, Wood G, Laydon A, Zidek A, Green T, Tunyasuvunakool K, Petersen S, Jumper J, Clancy E, Green R, Vora A, Lutfi M, Figurnov M, et al.: AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res 2022;50:D439-D444. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1061 |

||||

| 125 Krieger E, Vriend G: YASARA View-molecular graphics for all devices-from smartphones to workstations. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2981-2982. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu426 |

||||

| 126 Castellanos A, Andres A, Bernal L, Callejo G, Comes N, Gual A, Giblin JP, Roza C, Gasull X: Pyrethroids inhibit K2P channels and activate sensory neurons: Basis of insecticide-induced paraesthesias. Pain 2018;159:92-105. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001068 |

||||