Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000845

Accepted 13 January 2026 - Published online

23 January 2026

Tumor Destructive Mechanical Impulse (TMI) Treatment of Solid Tumors. Part II: Biomechanics, Computational Simulation, Technical Generator and Applicator Design, and Physiological Effect

bFraunhofer Institute for Microelectronic Circuits and Systems IMS, Duisburg, Germany,

cDepartment of Dermatology, Eberhard-Karls-University of Tübingen, Germany,

dInstitute of Applied Physics, Eberhard-Karls-University of Tübingen, Germany,

eInstitute of Immunology, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany,

fShepherd Center Wound Clinic, Piedmont Atlanta Hospital, Atlanta, GA, USA,

gInternational Neuroscience Institute, Hannover, Germany

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

To explore the feasibility and effectiveness of Tumor Destructive Mechanical Impulse (TMI) treatment of solid tumors, biomechanical preconditions for subsequent computational simulation of focused shock wave propagation within cells and tissue are investigated. This innovative “soft” approach is different from the FDA-approved high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)-based histotripsy, and from electrical Tumor Treating Fields (TTFs).Methods:

Atomic force microscopy investigation for cell mechanics, multiple parametric computational simulations for focused shock wave propagation, technical TMI generator and applicator design, light- and electron-microscopic evaluation of treatment effects on tumor cells and tissue.Results:

Individual tumor cell evaluation of physical properties as basis for multiple parametric simulations determine the optimal treatment parameters (total energy required, energy flux density, shock wave frequency) and applicator positions; design flexibility of applicator devices for extra- and intracorporeal treatment.Conclusion:

The fundamental feasibility, effectiveness and reliability of TMI treatment of solid tumors were proven, providing a reliable theoretical basis for the broadly applicable translation into clinical practice.Introduction

Our primary intention was to search for an innovative option to treat malignant tumors using a physical method which is not toxic, bears no radiation risk, is not or only mildly traumatic, relies on clear physical rules and engineering standards, and is cheap and simple enough that it can be applied in general hospitals and not only in sophisticated clinical centers.

Therapeutic propagation of alternating mechanical fields – ultrasound waves or shock waves – aims to deliver high-energy pulses in a spatially coordinated manner. The aim is to transfer focused energy to target tumor tissue, whether superficially situated or deep-seated in the human body, without causing harm to surrounding tissues. The first author, A.E. Theuer, who is engineer with broad industrial experience of computational simulation of vibration technology, started physico-mechanical and engineering investigations on vibration-induced destruction of malignant cells, which was, for related questions about tumor biology, developed for clinical application together with G.F. Walter, resulting in basic patents [1-3].

Current physical approaches for tumor treatment: Histotripsy and Tumor Treating Fields

Ultrasound-based tumor treatment is characterized by a continuous wave typically with numerous periodic

oscillations within a narrow bandwidth, whereby the therapeutic effect did not meet our demands: only a

relatively small percentage of the polymorphous tumor cells had mechanical properties allowing for

oscillations

within the respective narrow bandwidth. However, ultrasound has gained increasing importance as an option

for

tumors treatment. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized a new high intensity focused ultrasound

(HIFU)-based technology termed histotripsy [4-8]. HIFU-histotripsy has an intended destructive impact on

tumor

cells by periodic oscillations at high frequencies and, thereby, may coagulate the tumor cells and their

specific proteins. Clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of histotripsy for the symptom

relief of

inoperable abdominal tumors (NCT07180706) and evaluating the treatment of primary and metastatic liver

tumors

(NCT04572633) are underway [9, 10].

Tumor Treating Fields (TTFs) are alternating electric fields of low-intensity and intermediate-frequency

(100-300 kHz) that exert physical forces on cancer cells, disrupt cancer cell replication by interference

with

the proper formation of the mitotic spindle and hinder cancer cell motility through regulation of

microtubule

and actin dynamics. TTFs may also induce immunogenic cell death resulting in enhanced antitumor efficacy

when

combined with anti-PD-1 therapy [11-13]. In Germany, clinical trials, the TIGER study (NCT03258021) and

the

TIGER PRO-active study (NCT04717739) for patients with glioblastoma multiforme receiving TTF therapy, are

underway [14-16].

Tumor destructive mechanical impulse (TMI) treatment

In so far sound waves are applied, histotripsy applying ultrasound waves is similar with TMI treatment

applying

shock waves, but quite different with regard to the physico-mechanical approach. TMI treatment applying

shock

waves - due to their singular pressure pulse - has no thermal effect. This physico-mechanical difference

between

ultrasound waves and shock waves has consequences for the respective therapeutic applicability.

TTFs applied concomitant with immune checkpoint inhibitors enhance immunogenic cell death. In some cases,

immune

checkpoint inhibitors may induce undesirable auto-aggression against healthy cells. TMI treatment applied

as

monotherapy with pressure and strains on tumor cells may induce an abscopal effect attacking the primary

tumor

as well as its metastases without disadvantageous side effects.

TMI treatment exploits rapid pressure fluctuations, including both compression and tensile phases, to

initiate

cavitation bubbles, shear forces, and localized micro-lesions inside tumors. The collapse of cavitation

bubbles

generates extremely high local stresses capable of affecting cell membranes, organelles, and extracellular

matrix components. TMI deliver short, high‑amplitude acoustic impulses to tumor tissue at low

frequencies

(1-30 Hz), the pressure amplitudes are particularly large, so that a splitting effect due to

nonlinearities of

the propagation medium, e.g. human tissue, occurs. This is followed by a comparatively small tensile wave

of

lower amplitude. The resulting negative pressure exerts strain on the cell membranes; overstretched

membranes

lead to immunologically presentable cell fragments without exerting an undesirable thermal effect. TMI

focused

shock wave treatment relies on clear physico-mechanical rules and engineering standards, is not toxic,

bears no

radiation risk, is not traumatic to surrounding tissue, and avoids extensive pressure load or extremely

high

temperature.

Based on experimental evaluation of cell mechanics and using multiple computational parametric simulation

models, we aim to elucidate underlying mechanisms by which TMI focused shock wave treatment exerts its

optimal

effects on tumor cells. TMI treatment in combination with standard cancer care regimens may replace other

modalities in comprehensive cancer care.

Materials and Methods

Biomechanics

For the quantification of mechanical properties, human fibroblasts and BLM melanoma cells were

investigated by

atomic force microscopy (AFM) [17]. Imaging of single cells was performed in the force mapping mode using

a

cantilever with a nominal spring constant of 0.02 N/m (BioLever, Olympus, Melville, NY) [18, 19]. For each

single cell a mean elastic modulus was calculated by averaging the local elastic modulus over the cell

area. To

minimize the influence of the underlying substrate, only elastic modulus values for cell areas with a

height

above 1 µm were considered. Mean elastic moduli of 19 cells were averaged to obtain one representative

elastic

modulus 〈E〉 for each cell line. The origins of the BLM human melanoma cell line and the FF 1699

human

fibroblast cell line are documented in the Physiological Effect section below. Based on the physical

values and

the geometry of the tumor cells determined by AFM, strains in tumor cells can be simulated.

Computational simulation

To ensure compatibility, standardization, and reproducibility across future clinical studies and involved

institutions, all modeling and simulation steps were performed using established, commercially available

software platforms. It is essential to prepare personalized DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in

Medicine) data with segmentation procedures and FEM (finite element model) analysis for each patient.

To ensure patient safety and reproducibility, patient-specific DICOM data were segmented using Simpleware

ScanIP® (Synopsys Inc.) and subsequently imported into ANSYS SpaceClaim (ANSYS® SpaiceClaim; version

2024.R2,

ANSYS Inc.) for geometry preparation. The resulting anatomical models were subsequently transferred into

ANSYS

Explicit Dynamics (ANSYS® Mechanical/Fluent/CFX, version 2024.R2, ANSYS Inc.) to simulate the propagation

of

shock waves. A finite element model (FEM) of the shock wave device was constructed and integrated within

the

same Explicit Dynamics simulation environment using ANSYS SpaceClaim, enabling coupled device-tissue

simulations

under clinical pressure wave forms. At the tissue border, an electrohydraulic shock wave generator is

incorporated into FEM through the ANSYS space-claim module.

The numerical solution of the FEM (finite element) propagation models provides the time function of the

pressure

fields at each point within the tissue. To investigate strain distributions in cellular structures, the

simulated pressure–time profile at the edges of the tumor region was extracted and applied to a microscale

FEM

representing individual cellular components. The model included detailed representations of the cell

membrane,

cytoplasmic fluid, actin filaments, microfilaments, microtubules, nuclear envelope, nucleoplasm, and

extracellular components. Thereby, the numerical solution of the FEM propagation models provides

patient-specific treatment parameters, including total energy required, energy flux density, shock wave

frequency, total number and sequence of shock waves as well as the optimal applicator position resulting

from

multiple parametric simulations.

In parallel, the original DICOM data were processed using MATLAB®/TABLIN and converted into the OnScale®

(formerly PZFlex, OnScale Inc.) simulation environment, an explicit time-domain solver

designed for

high-frequency pressure wave propagation analysis in complex biological media.

Technical generator and applicator design

TMI generators include electrohydraulic, electromagnetic, and piezoelectric systems; all deliver steep

pressure

fronts with a tensile tail that can induce intracellular cavitation within the tumor cells.

Electrohydraulic generator devices use spark discharges between submerged electrodes to produce a

broad

acoustic wave that is focused by a reflector into the target tissue. This approach was the earliest

clinical

platform, first used in lithotripsy for kidney stones and later adapted to musculoskeletal medicine. In

electrohydraulic shock wave generators, a single high-voltage spark discharge between submerged electrodes

produces a rapidly expanding plasma channel and a rapid expansion that generates the shock wave. The wave

form

typically follows a damped sinusoidal oscillation determined by the LC circuit made up of an inductor

which is

expressed by the letter L and a capacitor represented by the letter C. Typical capacitive discharge

frequencies

are 50-500 kHz depending on capacitor size and circuit inductance. The spectral components of a single

discharge

strongly influence cavitation dynamics. Spark-gap discharge in water creates a plasma bubble.

Higher-frequency

components contribute to the formation of stable cavitation nuclei and bubble oscillations, whereas

lower-frequency components favor the growth of larger vapor cavities. The violent collapse of these

cavitation

bubbles results in secondary shock waves, microjets, and localized high shear stresses, which

significantly

augment the biomechanical effects of the primary electrohydraulic pulse. Thus, the frequency

characteristics of

a single discharge are critically determinant of cavitation intensity and therapeutic outcome.

Electromagnetic systems generate impulses by displacing a conductive membrane with a rapidly

energized

coil. Lorentz-force membrane or coil-driven acoustic pulse are launched into a lens or reflector. The

resulting

planar shock wave can be focused with acoustic lenses or reflectors. These systems are valued for their

reproducibility and lack of electrode degradation. Their pulse characteristics (reproducible output,

intermediate focal volumes; cavitation controllable via energy and pulse profiling) can be tuned with high

precision, offering adaptability for different clinical targets.

Piezoelectric systems rely on arrays of piezoelectric crystals arranged in a spherical or

hemispherical

configuration, which can be triggered simultaneously or in phased sequence to focus mechanical energy with

high

spatial precision. Phased piezo array elements on a spherical cap generate converging pulses. Each element

expands and contracts at its intrinsic resonance frequency, and the combined wavefront converges at the

focal

point. Typical excitation frequencies are 0.5-1.5 MHz. These systems provide highly precise and

reproducible

focal characteristics with narrower frequency spectra. Although piezoelectric units typically deliver

lower

single-pulse energies, they allow refined targeting and electronic beam steering, qualities such as high

spatial

precision and small focus volumes, that are important in oncological applications. The cavitation can be

minimized or enhanced depending on drive settings.

TMI applicators can be designed for extracorporeal and intracorporeal use. The device for TMI focused

shock wave

treatment of malignant tumors is technically characterized by different standard components: capacitive

discharge control, shock wave generator, shock wave treatment applicator, reflector, and device location

system.

Physiological effect

For cellular experiments, shock waves were generated by a standard urologic lithotripter and transmitted

by a

focused shock wave applicator. The sample holder with the cells in suspension culture was fixed into the

focus

of the shock waves. For evaluating the effect of low frequency, human breast cancer MCF7 cells were

exposed to

pressure shocks of 1-3 Hz and afterwards stained with propidium iodide (PI) which is due to induced cell

membrane permeability incorporated by dead cells. PI-staining is a viability dye flow cytometry method and

is

used in oncology to evaluate the efficacy of anticancer drugs. Flow cytometric analysis of PI-stained

cells

provides a quantitative measure of the proportion of living and dead cells in a population. For evaluating

cytotoxicity and/or viability, respectively, various melanoma cell lines (BLM, WM3734, MeIR), HaCaT

immortalized

human keratinocyte cells and FF 1699 fibroblasts were treated and evaluated by applying a CASY cell

counter

(OMNI Life Science). The BLM human melanoma cell line was kindly provided by Friedegund Meier (Skin Cancer

Center at the University Cancer Centre and National Center for Tumor Diseases, and Department of

Dermatology,

University Dresden), the WM3734 human melanoma cell line was kindly provided by Meenhard Herlyn (Melanoma

Research Center, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia). The MeIR mouse melanoma cell line derived from a

C57BL/6

mouse [20]. The HaCaT immortalized human keratinocyte cell line was purchased from ATCC Cell Biology

Collection.

The cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity using RPMI 1640 medium

supplemented with

10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Potential mycoplasma infection of the cells was

regularly tested with the Venor GeM Classic Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Minerva Biolabs), and cells were

used for

experiments within two months of thawing from the frozen stock. The fibroblast FF 1699 cell line was

isolated

from human foreskin after routine circumcision; the cell line was isolated as described previously

[21-23].

For evaluation of the TMI treatment effect in the tissue context, human surgical samples of cutaneous

malignant

melanoma were treated with 1, 000 and 2000 shock waves, respectively, at a frequency of 4 Hz with an

energy flux

density of 0.35 mJ/mm2. The effect was evaluated in light microscopy, and for cell membranes

and

intracellular structures, including mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum membranes, in transmission

electron

microscopy.

Results

Biomechanics

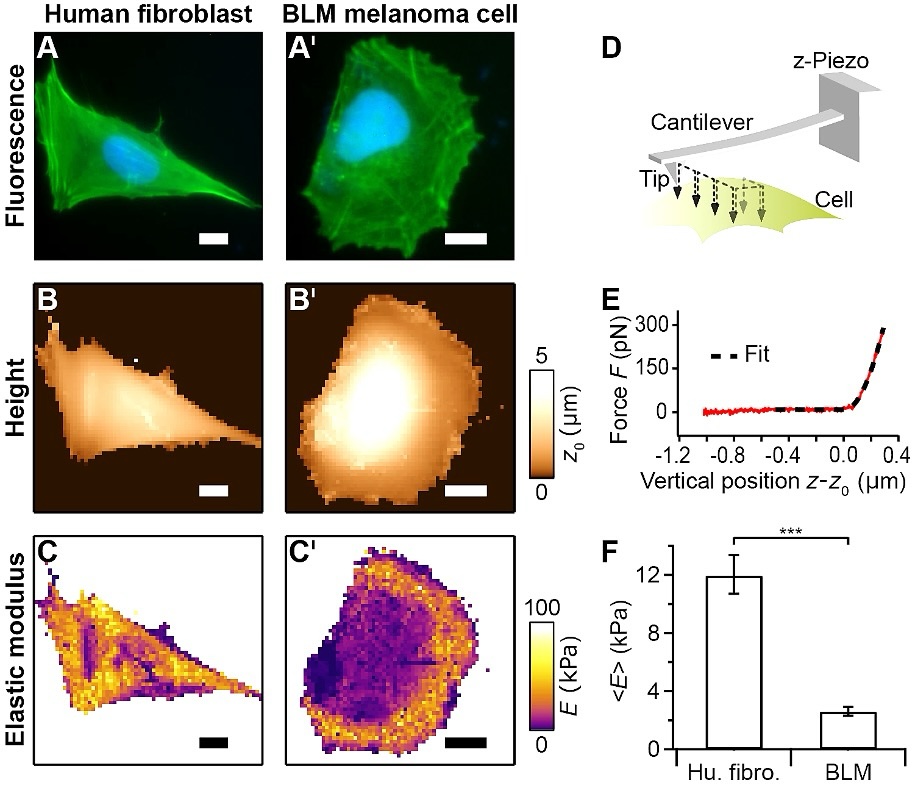

The mean elastic modulus is significantly lower for BLM melanoma cells than for human fibroblasts (Fig.

1). This

finding of softer cancerous cells in comparison to normal cells is in line with previous AFM studies [24].

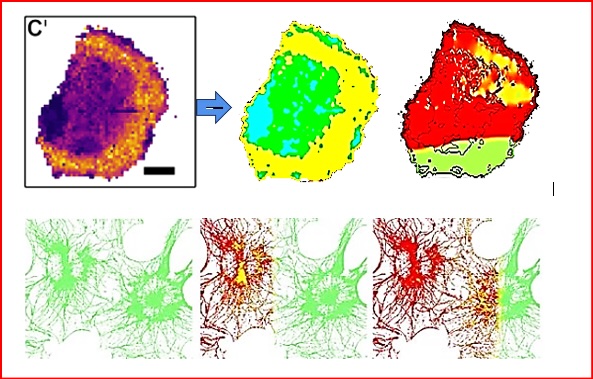

Based on these physical values and the geometry of the tumor cells determined by AFM, strains in tumor

cells can

be simulated by using the computational programs mentioned below for the computational simulation for

clinical

application. FEM models are particularly adequate for the mathematical description of the complex

processes of

shock wave propagation, since the distribution of strains during and after the shock wave propagation can

be

simulated on the cellular and the subcellular levels (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1: AFM investigation to compare the mechanical properties of human fibroblasts with BLM melanoma cells. A, A’: Optical fluorescence (actin green, cell nucleus blue). B, B’: AFM contact height. C, C’: AFM elastic modulus (softer regions are darker) for a human fibroblast (left column) and a BLM melanoma cell (right column). D: AFM force mapping principle whereby a 2D-raster pattern of force-distance curves is recorded on a cell. E: Force-distance curve (solid red curve) was fitted (dashed black curve) by applying Bilodeau's modified Hertz model for a pyramidal tip to obtain the local elastic modulus E [25]. F: In comparison to human fibroblasts, the geometric mean of the elastic modulus E (n = 19/group) of BLM melanoma cells is significantly lower (Student’s t-test, ***p<0.001). Error bars denote geometric SEM. The scale bar in the images is 20 µm.

Fig. 2: Above: BLM melanoma cell structure image imported from AFM (left) to FEM nonlinear shockwave propagation model (center) and shock wave propagation through the cell structures at 9 ns after induced shock waves at FEM model border (right). Below: After induced shock waves at FEM model border (left), simulation of shock wave propagation over time through cellular filamentous microstructure generating strains at t = 4 ns (center) and t = 8 ns (right).

Computational simulation

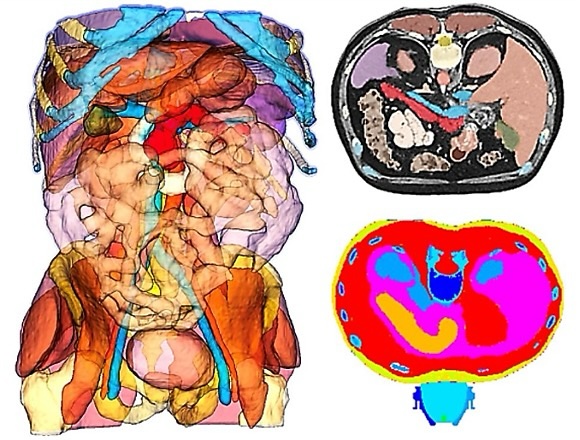

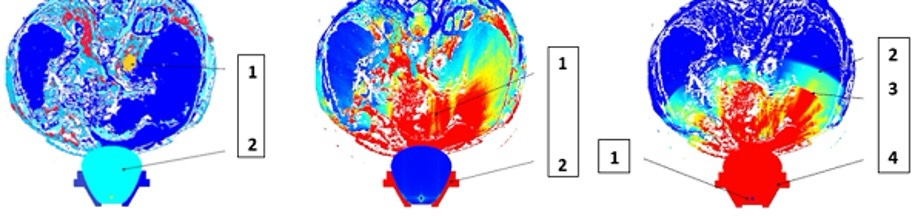

Simulating the DICOM/FEM data on basis of MRI/CT data of an individual patient can be visualized for

entire body

regions of that patient (Fig. 3). The shock waves propagate in an unfocused broad pressure front within

the body

and are eventually reflected and exert negative strains (Fig. 4). Technically it is possible to focus

the

wave

on the tumor target in a narrow propagation area, thereby optimizing the energy load within the tumor

tissue and

minimizing the energy load in the surrounding tissue. Optimizing electrode geometry, focused by an

ellipsoidal

reflector, discharge energy, and fluid conductivity allows for modulation of the discharge frequency

spectrum

(Fig. 5). Compared with higher-frequency discharges, the lower-frequency spectrum favors the growth of

larger

cavitation bubbles and results in a different distribution of secondary mechanical stresses within the

target

region. (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3: Left: Patient-specific DICOM data in 3D total segmentation. Right above: Patient-specific DICOM data in transversal segmentation at the level of the pancreas. Right below: Positioning of the electrohydraulic shock wave applicator for TMI treatment of a pancreatic carcinoma.

Fig. 4: Simulated effect of unfocused shock wave propagation. Left: Initial situation based on MRI/CT data. 1- patient DICOM/FEM data of an intrathoracic tumor (yellow), 2- shock wave generator. Center: Propagation of discharged shock waves. 1- exerting positive pressure, 2- reflector of the electrohydraulic device. Right: After discharge. 1- generator, 2- primary wave, 3- reflected wave exerting negative strains, 4- reflector.

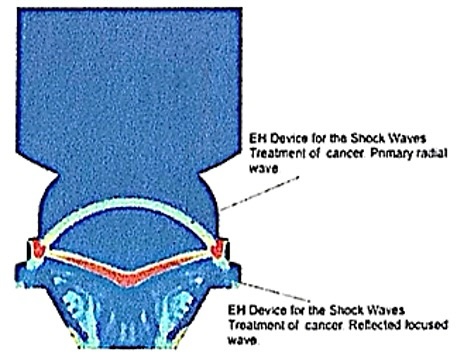

Fig. 5: Electrohydraulic device for the propagation of shock waves with the primary radial wave and the reflected focused wave.

Fig. 6: TMI focused shock wave propagation for targeting circumscribed tumor tissue. The shock wave propagation is generated by an electrohydraulic device with a discharge frequency of approximately 150 kHz.

Technical generator and applicator design

Technical improvements of TMI for the application in patients suffering from malignant tumors have been

designed

and patented by the first author [26]. For clinical applications, in most cases extracorporeal devices

can

be

used, whereby the design of the applicator can be optimally adapted to the targeted anatomical site of

the

tumor

tissue to be treated. Even transcranial application for the treatment of intracranial tumors is

possible.

Direct

transcranial treatment of superficial tumors is possible. For deep-seated tumors, the arrangement of

multiple

applicators in a ring shape can focus the energy within the tumor and minimizes the energy load in the

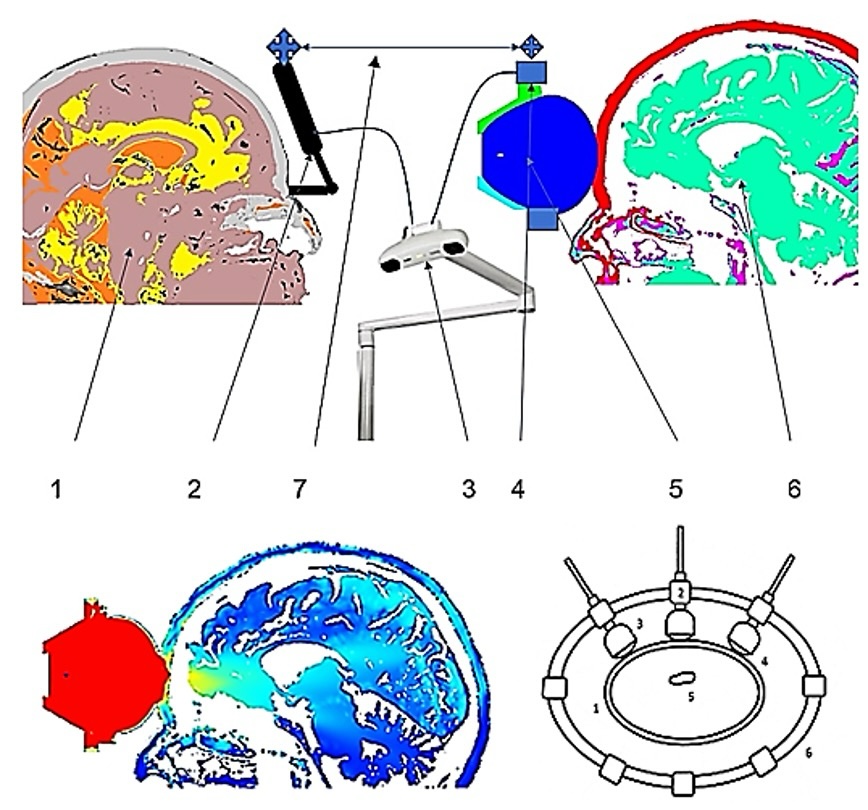

surrounding brain tissue (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: Above: Components of a device for extracorporeal soft focused shock wave treatment of brain tumors. 1- patient DICOM data, 2- patient rigid body, 3- optical localization, 4- treatment applicator rigid body, 5- applicator, 6- DICOM-MATLAB-ONSCALE-FEM simulation model, 7- DICOM-MATLAB-ONSCALE conversion. Below left: Single applicator; patient DICOM data for the MATLAB-ONSCALE-FEM simulation analysis for shock wave propagation within the area of a frontal brain tumor (yellow). Below right: Multiple applicators arranged in a ring shape for the treatment of intracranial tumors. 1-bone, 2-positioning device, 3 and 4-TMI devices, 5-tumor tissue, 6-positioning ring.

Physiological effect

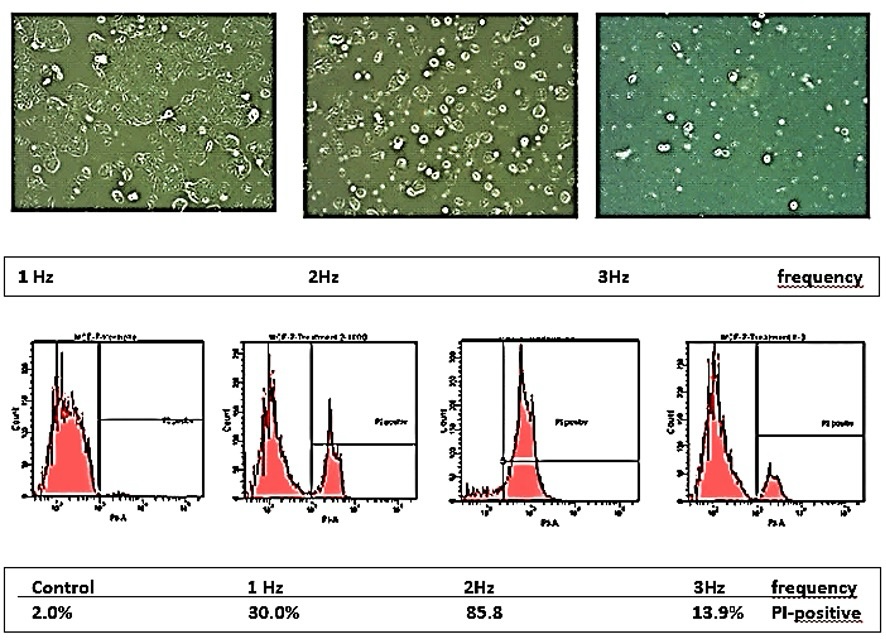

MCF7 cells. The sensitivity of the MCF7 cells to pressure shocks of 1 to 3 Hz appears to be

frequency

dependent, the highest rate of dead tumor cells was observed at 2 Hz (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Selective damaging of MCF7 tumor cells exposed to shock wave treatment cells at pressure shocks of 1-3 Hz and energy flux density of 1.24 mJ/mm2. Above: PI-staining with dead cells taking up the dye. Below: Percentage of MCF7 cells incorporating PI dye.

BLM melanoma cells

BLM melanoma cells were compared with human HaCaT cells, a spontaneously immortalized human keratinocyte

line.

At frequencies from 1 to 4 Hz the cytotoxicity rate for the BLM cells was between 20% (3 Hz) and 60% (4

Hz), for

HaCaT keratinocytes between 10% (1 Hz) and 25% (2Hz). The results represent the means of data from five

(BLM)

and three (HaCaT) independent experiments.

WM3734 melanoma cells. WM3734, a tumorigenic metastatic primary melanoma cell line, and FF 1699

fibroblasts were exposed to 2 Hz pressure shock waves at an energy flux density of 1.24

mJ/mm2.

The

WM3734 melanoma cells showed a significantly higher cytotoxicity rate (up to 40% after 30 minutes of

treatment)

than FF 1699 fibroblasts (below 10%).

MeIR melanoma cells. MeIR melanoma cells, a vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cell line, were

exposed

to TMI

focused shock wave treatment. Vemurafenib is an inhibitor of oncogenic BRAF kinase indicated for the

treatment

of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. All MeIR cells were

destroyed

(100%) at a pressure shock frequency of 2 Hz and energy flux density of 1.24 mJ/mm2, while

only

few

FF 1699 fibroblasts (11.7%) were destroyed.

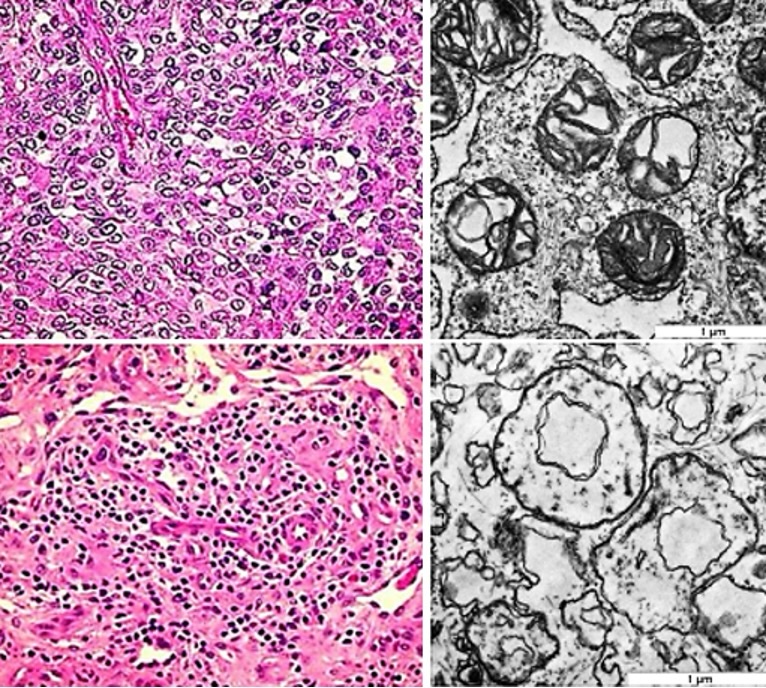

Human melanoma tissue. In light microscopy of treated human melanoma tissue, the most conspicuous

change

was an allover karyopyknosis indicating apoptosis. In electron microscopy, cell membranes and especially

membranes of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum treated with 1, 000 shock waves were disrupted, and

applying

treatment with 2000 shock waves conspicuously affected by strain (Fig. 9). Further, a series of

exposures

of BLM cells and FF 1699 fibroblasts to TMI shock wave treatment showed that in both cell lines a

certain

percentage of apoptotic impairment occurred (between 15 and 60% in BLM cells, between 15 and 40% in

FF1699

cells) dependent on different pressure shock frequencies (3 Hz and 4 Hz) and energy flux density (0.25

and

0.35

mJ/mm2), and especially on the number of shock waves applied (500, 1, 000, 2, 000 and 4,

000).

Fig. 9: Left: Untreated surgical sample of cutaneous malignant melanoma (above) and treated tissue (below) exhibiting pyknotic nuclei and eosinophilic changes of the fibrous matrix indicating apoptotic impairment (hematoxylin-eosin staining). Right: Ultrastructural disruption of BLM melanoma cells treated with 1,000 shock waves (above) and severe alterations after 2,000 shock waves (below) at 4 Hz with an energy flux density of 0.35 mJ/mm2 . The mitochondria are disrupted, the membrane strain increasing with the number of applied shock waves (transmission electron microscopy).

Discussion

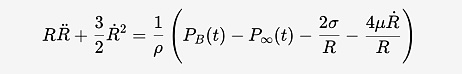

In malignant tumors, nuclear polymorphism including polyploid multinucleated giant cells occurs. In normal cells and tumor cells, the nucleus and the overall architecture of the cytoskeleton influence cell mechanics [27, 28], particularly the highly dynamic and cross-linked cytoskeletal structure of actin filaments and microtubules in the cytoplasm [29]. The cytoskeletal structure is disturbed, resulting in clumped and less bundled actin filaments on the inner surface of the cell membrane [30]. There is a distinct dynamic behavior of malignant and healthy cells. Polarized epithelial cells can undergo a transition characterized by the loss of cell-cell junctions and increased migratory activity into non-polarized invasive cells. Such transitions have been linked to cancer cell metastasis [31]. By palpation, obviously due to tumor stroma, tumors appear more rigid than their surrounding environment. Paradoxically, comparing the mechanics of individual normal and cancer cells, individual cancer cells are softer than their healthy counterparts on average [32]. The primary technical objective of the TMI focused shock wave propagation is to calculate and to ascertain precise pressure fields at all points of the treated tumor tissue and the quantity of absorbed energy throughout the entire treatment. This prevents damage to the surrounding healthy tissue and guarantees patient safety. Computational analysis of shock wave propagation in cellular structures based on AFM-data shows that the cytoskeletal filaments of malignant tumor cells stretch significantly more than those in healthy cells after the first shock wave impingement. The rate of re-stretching of tumor cells is slower than that of healthy cells. The second and subsequent shock waves, delivered before complete re-stretching, lead to additional disruptive stretching. In malignant tumors, mechanical changes are driven by expansion of the growing tumor mass as well as by alterations to the material properties of the surrounding extracellular matrix. Tumors often tend to be stiffer than the surrounding uninvolved tissue, yet the tumor cells themselves are often softer than the healthy cells. The stretching rate is critical in the apoptotic impairment of tumor cells. Another biophysical mechanism of TMI treatment is intracellular cavitation. Cavitation evoked by TMI, the rapid collapse of intracellular microbubbles following a pressure drop, leads to localized high shear forces and microjets capable of mechanically disrupting, boiling or lysing tumor cells. Modeling studies simulate how tissue properties modulate cavitation thresholds and bubble dynamics. Incorporating tissue viscoelasticity and inhomogeneity is essential in accurately predicting cavitation behavior in vivo [33, 34]. Realistic cavitation modeling must consider dense bubble clouds where bubble-bubble interactions significantly influence collapse dynamics. In bubble clouds, collective effects lead to enhanced local pressures, a factor important in explaining enhanced therapeutic effects [35, 36]. Spherical bubble behavior in incompressible, viscous liquids can be calculated by using the Rayleigh-Plesset equation [37, 38] and its extensions (Fig. 10). This model can be extended by the Keller-Miksis [39] or Gilmore-Akulichev [40] equations to account for compressibility and shock wave propagation effects relevant to TMI treatment. We as treating physicians are inclined to measure the success of the treatment by the rate of destroyed tumor cells, e.g., as seen and calculated in the propidium iodide (PI) staining where PI is incorporated by dead tumor cells. A high percentage of PI-stained dead cells is understood in oncology as sign of efficacy of anticancer drugs. In contrast, it is suggested that instead only looking for dead tumor cells, we should focus our attention on the (still) viable cells. Still viable tumor cells after TMI treatment are also affected by pressure and tension, but now, obviously unmasked for the patient’s individual adaptive immune system, they may present tumor-specific antigenic proteins to the adaptive immune system, thereby triggering an immunological response. We tested this assumption in animal experiments and in first clinical applications of TMI focused shock wave treatment, and we were content to find our assumption confirmed [41]. Under TMI exposure, tumor cells undergo as well necrotic cell death as apoptosis. The relative contribution of necrosis or apoptosis depends on the magnitude and repetition rate of the applied mechanical impulses.

Fig. 10: Rayleigh-Plesset equation, where R is the bubble radius, PB(t) is the pressure inside the bubble, P∞(t) is the pressure in the surrounding liquid, ρ, μ, and σ are the liquid tensity, viscosity, and surface tension, respectively.

Necrotic cell death predominates in regions of metastases exposed to high-intensity mechanical stress. The abrupt transmission of pressure waves leads to pronounced shear forces and micro-deformations. These forces cause direct mechanical disruption of the cell membrane, cytoskeletal collapse, and rupture of intracellular organelles. The affected cell membrane integrity results in uncontrolled ion fluxes, rapid osmotic swelling, and mitochondrial dysfunction with a sudden depletion of cellular ATP. Tumor cells undergo immediate necrosis. This form of cell death is characterized by the release of intracellular components, including ATP, HMGB1, nucleic acids, and other danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [42, 43]. TMI-induced apoptosis is observed in tumor cells exposed to submaximal but biologically effective mechanical impulses. In these regions, TMI-induced mechanical stress results in mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. This initiates the intrinsic apoptotic cascade, with subsequent caspase activation, DNA fragmentation, and controlled cellular dismantling [44]. TMI-induced apoptotic cell death proceeds without immediate membrane rupture and is therefore presenting immunogenic proteins to the adaptive immune system for a prolonged time.

Conclusion

TMI focused shock wave treatment reliably induces overstretching of tumor cell membranes leading to disruptive impairment of tumor cells and eventually to apoptosis. By still viable tumor cells specific immunological responses can be initiated. It is possible to determine optimal treatment parameters by computational simulation.

TMI focused shock wave treatment may, in combination with existing treatment modalities, be seen as an additional option for comprehensive cancer care.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The development of specific computational simulation programs by A.E. Theuer was supported by

AiF Arbeitsgemeinschaft industrieller Forschungsvereinigungen (grant number KF3356302AK4), and by

Zentrales Innovationsprogramm Mittelstand (grant number ZF4803001BA9).

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of experimental results are available from the corresponding author

upon

reasonable request.

Author Contributions

A.E. Theuer and G.F. Walter, with support from F. Lang, initiated investigations into the TMI treatment

of

malignant tumors.

A.E. Theuer elaborated the computational parameters for simulation and drew up the engineering

preconditions for

the construction of application devices.

A.E. Theuer and G.F. Walter conceptualized and proved the principal biological feasibility of TMI

treatment of

malignant tumors.

N. Schierbaum and T. Schäffer performed and evaluated the atomic force measurements.

H. Niessner and T. Sinnberg evaluated cell reactions to shock wave treatment by flow cytometric analysis

and

provided clinical background for the design of application devices.

H. Niessner, T. Sinnberg, T.K. Eigentler and J.D. Mullins transformed the concept into the actual

clinical

application of TMI focused shock wave treatment for patients suffering from malignant tumors.

G.F. Walter wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

| 1 | Theuer AE, Walter GF: Device and arrangement for destroying tumor cells and tumor tissue. German

Patent WO002009156156A1 / 2009.

|

| 2 | Theuer AE, Walter GF: Apparatus for the destruction of tumor cells or pathogens in the blood

stream. German Patent WO002010406A1 / 2010.

|

| 3 | Theuer AE, Walter GF: Medical device for treating tumor tissue. German Patent WO002010049176A1 /

2010.

|

| 4 | Bader KB, Vlaisavljevich E, Maxwell AD: For whom the bubble grows: physical principles of bubble

nucleation and dynamics in histotripsy Ultrasound Therapy. Ultrasound Med Biol 2018;45:1056-1080.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.10.035 |

| 5 | Bachu VS, Kedda J, Suk I, Green JJ, Tyler B: High-intensity focused ultrasound: a review of

mechanisms and clinical applications. Ann Biomed Eng 2021;49:1975-1991.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-021-02833-9 |

| 6 | Xu Z, Hall TL, Vlaisavljevich E, Lee FT Jr: Histotripsy: the first noninvasive, non-ionizing,

non-thermal ablation technique based on ultrasound. Int J Hyperthermia 2021;38:561-575.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2021.1905189 |

| 7 | Williams RP, Simon JC, Khokhlova VA, Sapozhnikov OA, Khokhlova TD: The histotripsy spectrum:

differences and similarities in techniques and instrumentation. Int J Hyperthermia

2023;40:2233720.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2023.2233720 |

| 8 | Matthews MJ, Stretanski MF: Ultrasound Therapy. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL,

2024.

|

| 9 | To Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Histotripsy for the Symptom Relief of Inoperable

Abdominal

Tumors. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT07180706.

|

| 10 | The HistoSonics System for Treatment of Primary and Metastatic Liver Tumors Using Histotripsy

(#HOPE4LIVER US). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04572633.

|

| 11 | Kirson ED, Gurvich Z, Schneiderman R, Dekel E, Itzhaki A, Wasserman Y, Schatzberger R, Palti Y:

Disruption of cancer cell replication by alternating electric fields. Cancer Res

2004;64:3288-3295.

https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0083 |

| 12 | Voloshin T, Schneiderman RS, Volodin A, Shamir RR, Kaynan N, Zeevi E, Koren L, Klein-Goldberg A,

Paz R, Giladi M, Bomzon Z, Weinberg U, Palti Y: Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) hinder cancer

cell

motility through regulation of microtubule and actin dynamics. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:3016.

https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12103016 |

| 13 | Voloshin T, Kaynan N, Davidi S, Porat Y, Shteingauz A, Schneiderman RS, Zeevi E, Munster M, Blat

R, Tempel Brami C, Cahal S, Itzhaki A, Giladi M, Kirson ED, Weinberg U, Kinzel A, Palti Y:

Tumor-treating fields (TTFields) induce immunogenic cell death resulting in enhanced antitumor

efficacy when combined with anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2020;69:1191-1204.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-020-02534-7 |

| 14 | TTFields In GErmany in Routine Clinical Care (TIGER).

https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03258021.

|

| 15 | TIGER PRO-Active - Daily Activity, Sleep and Neurocognitive Functioning Study.

https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04717739.

|

| 16 | Khagi S, Kotecha R, Gatson NTN, Jeyapalan S, Abdullah HI, Avgeropoulos NG, Batzianouli ET,

Giladi

M, Lustgarten L, Goldlust SA: Recent advances in Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy for

glioblastoma. Oncologist. 2025;30:oyae227.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyae227 |

| 17 | Li M, Xi N, Wang YC, Liu LQ: Atomic force microscopy for revealing micro/nanoscale mechanics in

tumor metastasis: from single cells to microenvironmental cues. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021;42:323-339

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-020-0494-3 |

| 18 | Jiao Y, Schäffer TE: Accurate height and volume measurements on soft samples with the atomic

force

microscope. Langmuir 2004;20:10038-10045.

https://doi.org/10.1021/la048650u |

| 19 | Schächtele M, Kemmler J, Rheinlaender J, Schäffer TE: Combined high-speed atomic force and

optical

microscopy shows that viscoelastic properties of melanoma cancer cells change during the cell

cycle.

Adv Materials Technol 2021;2101000.

https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202101000 |

| 20 | Murphy BM, Jensen DM, Arnold TE, Aguilar-Valenzuela R, Hughes J, Posada V, Nguyen KT, Chu VT,

Tsai

KY, Burd CJ, Burd CE: The OSUMMER lines: A series of ultraviolet-accelerated NRAS-mutant mouse

melanoma cell lines syngeneic to C57BL/6 Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2023;36:365-377.

https://doi.org/10.1111/pcmr.13107 |

| 21 | Meier F, Schittek B, Busch S, Garbe C, Smalley K, Satyamoorthy K, Li G, Herlyn M: The

RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways present molecular targets for the effective

treatment of advanced melanoma. Front Biosci 2005;10:2986-3001.

https://doi.org/10.2741/1755 |

| 22 | Lasithiotakis KG, Sinnberg TW, Schittek B, Flaherty KT, Kulms D, Maczey E, Garbe C, Meier FE:

Combined inhibition of MAPK and mTOR signaling inhibits growth, induces cell death, and abrogates

invasive growth of melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol 2008;128:2013-2023.

https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2008.44 |

| 23 | Sinnberg T, Lasithiotakis K, Niessner H, Schittek B, Flaherty KT, Kulms D, Maczey E, Campos M,

Gogel J, Garbe C, Meier F: Inhibition of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling sensitizes melanoma cells to

cisplatin and temozolomide. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:1500-1515.

https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2008.379 |

| 24 | Schierbaum N, Rheinlaender J, Schäffer TE: Viscoelastic properties of normal and cancerous human

breast cells are affected differently by contact to adjacent cells. Acta Biomater 2017;55:239-248.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2017.04.006 |

| 25 | Bilodeau GG: Regular pyramid punch problem. J Appl Mech 1992:59:519-523.

https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2893754 |

| 26 | Theuer AE, Theuer I: Device for treating malignant diseases with the help of tumor-destructive

mechanical pulses (TMI). U.S. Patent US20200038694 / 2023.

|

| 27 | Denais C, Lammerding J: Nuclear mechanics in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 2014;773:435-470.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_20 |

| 28 | Grady ME, Composto RJ, Eckmann DM: Cell elasticity with altered cytoskeletal architectures

across

multiple cell types. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2016;61:197-207.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.01.022 |

| 29 | Ketene AN, Roberts PC, Shea AA, Schmelz EM, Agah M: Actin filaments play a primary role for

structural integrity and viscoelastic response in cells. Integr Biol (Camb) 2012;4:540-549.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ib00168c |

| 30 | Calzado-Martín A, Encinar M, Tamayo J, Calleja M, San Paulo A: Effect of actin organization on

the

stiffness of living breast cancer cells revealed by peak-force modulation atomic force microscopy.

ACS Nano 2016;10:3365-3374.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b07162 |

| 31 | Vargas DA, Bates O, Zaman MH: Computational model to probe cellular mechanics during

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cells Tissues Organs 2013;197:435-444.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000348415 |

| 32 | Alibert C, Goud B, Manneville JB: Are cancer cells really softer than normal cells? Biol Cell

2017;109:167-189.

https://doi.org/10.1111/boc.201600078 |

| 33 | Zhong P, Chuong CJ: Propagation of shock waves in elastic solids caused by cavitation microjet

impact. I: Theoretical formulation. J Acoust Soc Am 1993;94:19-28.

https://doi.org/10.1121/1.407077 |

| 34 | Zhong P, Chuong CJ, Preminger GM. Propagation of shock waves in elastic solids caused by

cavitation microjet impact. II: Application in extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. J Acoust Soc

Am 1993;94:29-36.

https://doi.org/10.1121/1.407088 |

| 35 | Lokhandwalla M, Sturtevant B: Mechanical haemolysis in shock wave lithotripsy (SWL): I. Analysis

of cell deformation due to SWL flow-fields. Phys Med Biol 2001;46:413-37.

https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/46/2/310 |

| 36 | Lokhandwalla M, McAteer JA, Williams JC Jr, et al. Mechanical haemolysis in shock wave

lithotripsy

(SWL): II. In vitro cell lysis due to shear. Phys Med Biol 2001;46:1245-64.

https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/46/4/323 |

| 37 | Strutt JW 3rd Baron Rayleigh: On the pressure developed in a liquid during collapse of a

spherical

cavity. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Series 6,

1917;34:94-98.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440808635681 |

| 38 | Plesset MS: The dynamics of cavitation bubbles. J Appl Mechan 1949;16:228-231.

https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4009975 |

| 39 | Fourest T, Deletombe E, Faucher V, Arrigoni M, Dupas J, Laurens JM: Comparison of Keller-Miksis

model and finite element bubble dynamics simulations in a confined medium. Application to the

Hydrodynamic Ram. Eur J Mechan - B/Fluids 2018;68:66-75.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechflu.2017.11.004 |

| 40 | Zhong H: Comparison of Gilmore-Akulichev equation and Rayleigh-Plesset equation on therapeutic

ultrasound bubble cavitation. MSc Thesis, Iowa State University Ames, Iowa, 2013.

|

| 41 | Theuer AE, Thomas I, Lang F, Borkmann M, Mullins JD, Eigentler TK, Walter GF: Tumor destructive

mechanical impulse (TMI) treatment of solid tumors. Part I: Animal experiments, clinical

application

and immunological abscopal effect. Cell Physiol Biochem 2025;59:800-810.

https://doi.org/10.33594/000000828 |

| 42 | Murao A, Aziz M, Wang H, Brenner M, Wang P. Release mechanisms of major DAMPs. Apoptosis

2021;26(3-4):152-162.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-021-01663-3 |

| 43 | Chen F, Tang H, Cai X, Lin J, Kang R, Tang D, Liu J. DAMPs in immunosenescence and cancer. Semin

Cancer Biol 2024;106-107:123-142.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2024.09.005 |

| 44 | Nagata S. Apoptosis and clearance of apoptotic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2018;36:489-517.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053010 |